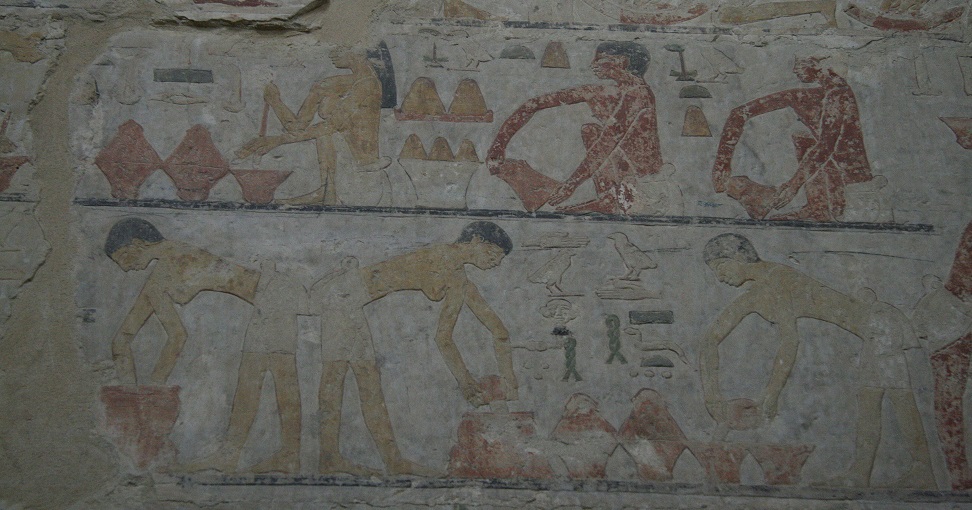

Egyptian art had a magical-functional purpose and did not take into consideration the figure of the spectator.

For that reason, we cannot consider Egyptian art from just an aesthetic empiricism. Which makes art feel in a subjective way through sensations.

We must read the Egyptian Art from the technical realization, but also from its ideological-religious motivation, a motivation of a social group that gives the work a collective nature.

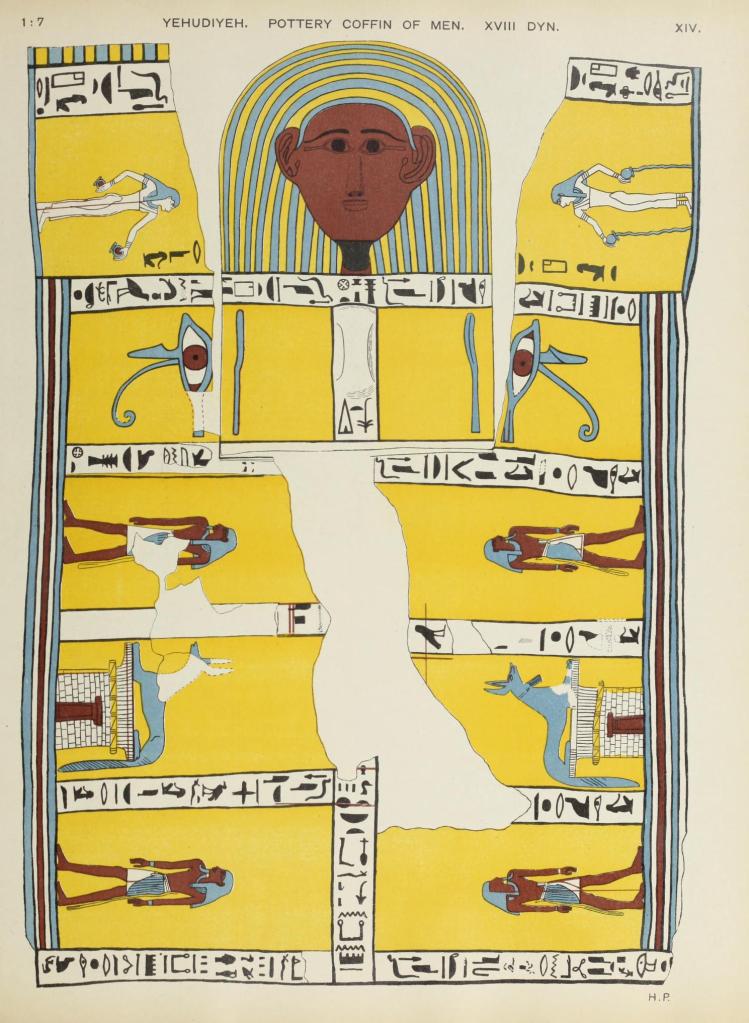

Egyptian Art is Objects and Texts.

In ancient Egypt written language and figurative language go together. Usually the images reach where the texts do not arrive and vice versa. For that reason, Objects in Egyptian art must be “read”, as if they were manuscripts or inscriptions.

The art of ancient Egypt is neither as transparent nor as natural as it seems at first sight. Egyptian Art is a figurative art that does not always present evidence and whose images often contain codified information.

Statue of Ramses II from Tanis.

We have a good example in a statue of Ramses II, from Tanis and now in the Cairo Museum At first glance, it is an image of Ramses II child protected by the figure of the god Huron.

However, this, which is pure iconography, has an iconology that turns this statue into a true cryptogram in three dimensions.

Ramses II from Tanis. Cairo Museum. Photo: Panoramio

Reading literally every part of this sculpture, we get the following:

• The solar disk that appears on the head of Ramses is “Ra” in Ancient Egyptian.

• The image of Ramses is that of a child and follows the protocol of the infantile effigies: the finger of the right hand to the mouth. We should read this part of the statue as “mes”, which means “child” in Egyptian.