We have seen throughout this work that the mourners’ hair (locks, mane, dishevelled, plaits) played a very important role in the funerary ceremony of ancient Egypt. We have also seen that sometimes those different aspects of the hair had just a symbolic meaning from a resurrection point of view (as for instance the two ringlets wprty). We also know now that there were two types of mourners: those ones being in a group in the procession accompanying the corpse and the two women impersonating Isis and Nephtys and in charge of the deceased’s rebirth.

The two priests and one mourner (the wife according to the inscription) in the Opening of the Mouth of Roy. Painting from the tomb of Roy in Dra Abu el-Naga. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

According to the sources the hair of these two mourning women was important from many points of view: symbolic, mythic and ritual. From the Egyptian iconography and texts we can discern a mourning rite in which the two women made a gesture with their hair or lock of hair over the mummy with a regenerating goal, and we can also guess a practice of shaving or cutting hair to the two mourners that happened in some moment at the end of the funerals when the deceased’s rebirth was a fact.

After the embalming of the corpse, the cortège walked to the necropolis, once there took place the main Egyptian rite for the benefit of the dead: the Opening of the Mouth ceremony, which consisted in a group of gestures for transmitting vitality to the mummy (this way the deceased recovered the ability of breathing, seeing, hearing…), and the two representatives of Isis and Nephtys took part in that process. Many sources reflect this ritual, but usually they are not too explicit. It is mostly represented in a shorten way, with the lector priest and/or the sem priest holding the utensils used for the ritual (mainly the adze and the stone vessels) and officiating on the mummy, meanwhile two mourners or sometimes just one, cry close to the dead. In some cases the scene has a more divine nuance and the one officiating is Anubis, while Isis and Nephtys stay at both extremes of the corpse.

Anubis, Isis and Nephtys in the Opening of the Mouth rite. Painting from the tomb of Nakhtamon in Deir el-Medina. XIX Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

The most explicit document about the Opening of the Mouth ceremony that ancient Egyptians have left to us is the representation in the south wall on the tomb of Rekhmire. In a composition of fifty three scenes the artist showed the rite step by step.

The broad outline which Rekhmire offers would be:

1. The mummy or deceased’s statue (as it is the case in Rekhmire’s tomb) is put on a mound symbolising the primeval hill.

2. The mummy/statue is purified with water, natron and incense.

3. The sem priest transmits the vital energy rememorizing the ancient Egyptian tradition of the sacrifice and rebirth of the tekenu. The sem priest imitated the ancient victim curled up and wrapped in a clothing, he came up from it and had a small dialogue with the lector priest:

Sem priest: “I saved the eye from his mouth, I healed his leg”

Lector priest: “I have placed your eye, through which you revive”[1].

4. The sem priest makes the first gestures of Opening the Mouth with the little finger.

5. The mesentiu (labourers) work on the statue (polishing and carving) as a creational gesture[2].

6. Sacrifice of the ox of Upper Egypt for restoring the vitality of the deceased. The sem priest offers the animal’s heart and foreleg to the mummy/statue. One of the mourners (the big Dyeret) is present:

Sem priest: “to stretch the arms towards the bull ng of Upper Egypt”

Slaughterer: “get up over him, cut its foreleg and remove its heart”

The big Drt says at his ear: “Your lips have done that against you. Will your mouth open?”

Sacrifice of the ox with the presence of the mourner. Painting from the tomb of Rekhmire in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

This part of the ceremony is very important for us, not just because of the presence of one of the mourners, but also because it seems to remind the conflict between Horus and Seth. According to J. C. Goyon the sequence would stage when these two gods fought and Isis became a kite, landed on a tree and cried to Seth, who denounced unconsciously his crime: “Cry over you. Your own mouth has said it. Your ability has judged you. What else?[3]

The idea is the same one as in the tekenu ceremony we have seen in the tomb of Mentuherkhepeshef: killing a victim and offering the foreleg and the heart… but what about the hair?

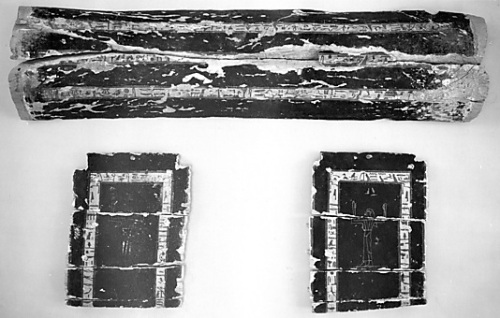

Funerary scene of the tomb of Montuherkhepeshef in Dra Abu el-Naga. XVIII Dynasty.

Maybe we should relate the lock of hair of the tomb of Mentuherkhepeshef with the presence of the mourner in the tomb of Rekhmire; and think that a mourner’s piece of hair was cut and offered join with the foreleg and the heart.

7. After the sacrifice the sem priest makes more gestures of opening the mouth to the mummy/statue with the utensils, and in one case with the ox’s foreleg. The finality was to keep in touch the whole of the head with those magical tools (the nTrt adze and the wr-HkAw).

8. The mummy/statue is given to the rpat, who represented the heir[4], and the mesentiu work again on it.

9. New gestures of opening the mouth to the deceased are made. After that, there is an offer of 3bt stones[5].

10. Sacrifice of the ox of Lower Egypt. Here again we have the presence of one mourner, the small Dyeret, and once more the animal’s foreleg and heart are offered to the dead one.

11. After the sacrifice the priest opens again ritually the deceased’s mouth.

12. Funerary offerings and the final resurrection is a fact (the sem priest pays his respects to the new soul who lives in the Hereafter).

According to Rekhmire’s tomb, the two mourners impersonating Isis and Nephtys took part in the Opening of the Mouth ceremony. TTA4 and TT53 have both scenes of sacrifice of an ox with the presence of one mourner. But it is also true that in some other cases there is no trace of mourning women in this rite, as we can see in the tomb of Menna[6]

Anyway, sources proof that the two mourners in the role of Isis and Nephtys made an important role in that ritual for the deceased’s resurrection. They were members of the group of personalities who took care of the rebirth of the corpse and who reproduced the myth of Osiris.

The Opening of the Mouth ceremony was a group of practices for giving the life back to the deceased assimilated to Osiris. The priests and the two mourners recreated the chapter of the legend where Horus avenges his father’s death at the hands of Seth. In the rite it is the moment of the animal sacrifice, the ox, as scapegoat, with the presence of the sem priest, the slaughterer and the two mourners. The animal’s foreleg and heart are offered to the dead one, but also a piece/lock of hair. At this point we must remember chapter 667 of the Coffin Texts, where the healing of the hair sm3 happens at the same time of the offering of the foreleg and the giving of breath. And the final resurrection happens when the lunar eye is reconstituted and offered as Udjat eye to the deceased. E. Otto assimilated the lunar eye with the foreleg and/or the heart of the animal victim[7]; for others the moon can also be a knife, a leg or a lock of hair[8].

Carrying the leg and the heart for the deceased. Painting from the tomb of Menna in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

Throughout this work we have seen the relationship in Egyptian belief between the hair and the lunar eye and how there is a clear coincidence between cutting mourner’s hair (cutting the s3mt or shaving the mourners) and giving the Udjat eye to the dead one. It is also interesting to notice the use in the Opening of the Mouth ceremony of the flint knife peseshkef, considered by scholars as a very ancient tool for cutting the umbilical cord.

The sacrifice of the ox represented the victory of Horus over Seth, it was also the moment of restoring the Udjat eye and, according to the funerary texts, shaving the mourners and/or cutting the s3mt. And New Kingdom iconography shows the mourners taking part in the Opening of Mouth ceremony and with no mane of hair after the rite.

But, do we really know why were these two women there, what did they really do or why their presence during the Opening of the Mouth is not so evident in iconography?

[2] This step would be made when the ceremony was made on a statue. In ancient Egypt the sculptor was called sankh, which meant “to make live”.

[3] J.C.Goyon, 1972, p. 121.

[4] It means “prince” (Wb II, 415, 15).

[5] Some scholars consider they symbolize the milk teeth.

[7] E. Otto, 1950, p. 171.

[8] Ph. Derchain, 1962, p.20.