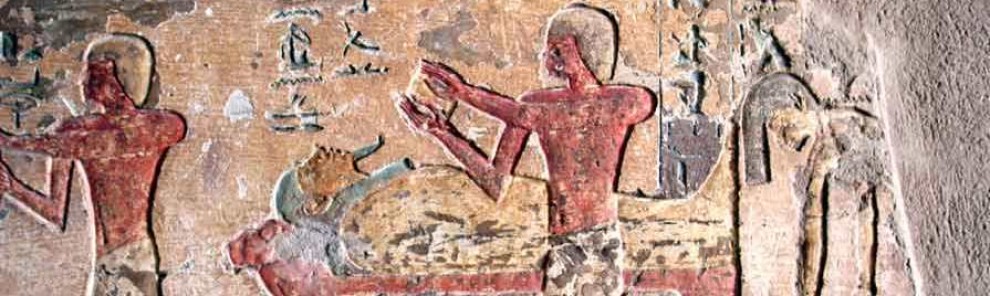

Serket from the tomb of Nefertari. XIX Dynasty. Valley of the Queens. Photo: www.jfbradu.free.fr

It has been always thought that the ancient Egyptian deity Serket was the Scorpion Goddess, whose power was in her stings.

Scholars considered that, due to the quality of killing with the poison, Serket was in Ancient Egypt an effective divine protection against poisonous bites.

Nowadays it is widely considered that in fact Serket was not a scorpion, but a nepid, that is a water scorpion.

Water scorpion. Photo: www.geoffpark.wordpress.com

The water scorpion is an insect which lives in the marshes and, whose appearance remembers the one of scorpions. The water scorpion looks like an earth’s scorpion due to the shape of its two forelegs and to a long breathing-tube at the end of the abdomen that looks like a sting.

Although morphologically they seem to be very close, the nepid is a harmless insect, while the scorpion is harmful and in some cases can cause death. The bite of a scorpion produces many damages, among them the asphyxiation; on its behalf the waterscorpion presents a breathing-tube at the end of the abdomen which allows t take air while the animal is under the water. So, Ancient Egyptians could have considered the water scorpion as the positive counterpoint of the lethal scorpion. They would be the both side of the same matter:

Serket. scorpion versus nepid

On the other hand, Serket is a name which comes from the verb srk:

On the other hand, Serket is a name which comes from the verb srk:

which means “breathe”, “make breathe” (Wb IV, 201). And Serket is the short version of the name of this goddess. Her complete name was srkt Htw:

This ancient Egyptian name meant: “she makes breathe the windpipe”.

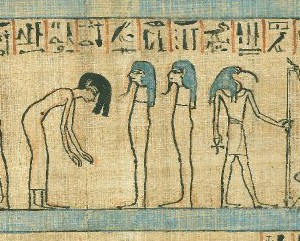

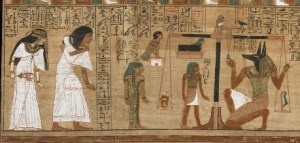

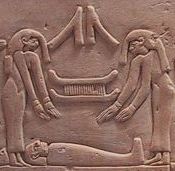

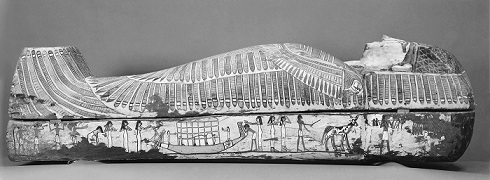

Among the faculties the dead (assimilated to Osiris) needed for coming back to his new life, was the breath. According to the belief of ancient Egypt, it was Isis the goddess who blew air to the nostrils of Osiris by beating her wings. And Serket was eventually assimilated to Isis.

Isis as a kite flaps wings and put herself over her husband. Relief from the temple of Seti I in Abydos. XIX Dynasty. Photo: http://www.passion-egyptienne.fr

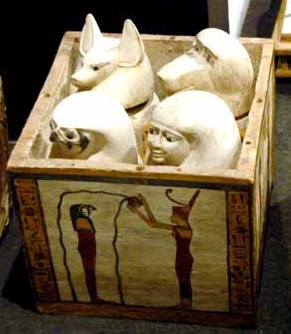

This exposure makes us think of the posibility that ancient Egyptians included Serket in the team for protecting the corpse thanks to her faculty for allowing the breathing.