We have already seen how in chapter 180 of Book of the Dead the mourners appear dishevelled for or over the deceased.

The dead is now in the Hereafter and needs to get again the mobility. This chapter treats about the physical resurrection of the deceased and it was included in many tombs of kings (Tutmosis III, Seti I, Ramses II, Meneptah I, Seti II, Siptah, Ramses III and Ramses IV). In all cases the verb used for dishevelled was nwn. Taking into consideration those determinatives and the iconography of tombs of Amenemhat and Renni, one correct translation could be “…they are dishevelled over you…”.

We can then visualize the nwn gesture over the corpse for his benefit. Because after that the chapter follows: “…your soul gets happy, your body becomes glorious…” It describes the resurrection of the mummy, process in which was important that rite of mourning.

At this point we need to mention three relevant documents that refer to the role of mourning women in front of the body.

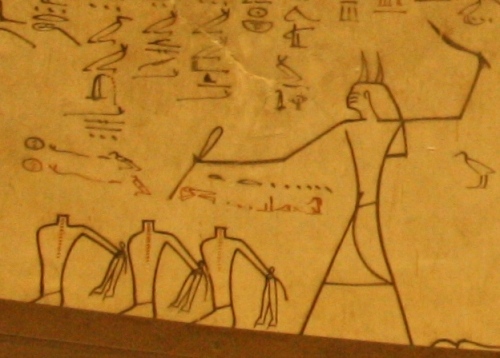

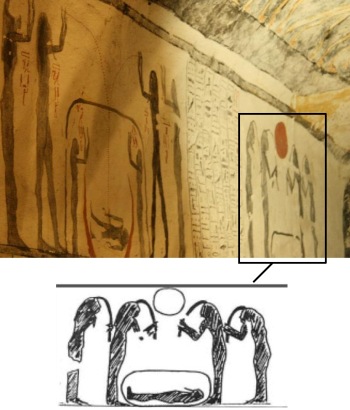

1) The tomb of Ramses IX. On the left wall of the funerary chamber there is a unique scene of resurrection. The dead as a mummy inside an oval, over the corpse four women are making the nwn m gesture of pulling their locks of hair.

Women pulling lock of hair over the dead. Tomb of Ramses IX. Valley of the Kings. XX Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

In the following scene the dead is not a mummy anymore, but now his legs and arms have movement. That makes us think about the nwn m gesture as something made for revitalising the body. The text accompanying the image is a fragment of the Book of Caverns in which we read about the resurrection of the dead and in that context it says:

“Those Goddesses are so, they are mourning over the secret place of Osiris…they are together, screaming and crying over the secret place of the ceremony…their secret is in their fingers…”

It is clear the relationship between mourning and the resurrection of the dead, to whom the women are pulling their locks of hair. On the other hand it is interesting to pay attention to the expression “…their secret is in their fingers…”, because with those fingers they are holding their hair. Which one is the secret? Is the resurrection or the way for reaching that resurrection?

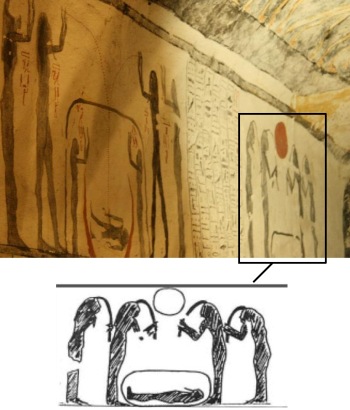

2) The coffin of Ramses IV. In the head piece there is a representation of Isis and Nephtys making the same nwn m gesture.

Isis and Nephtys pulling their locks of hair. This image is on the head piece of the coffin of Ramses IV.

Both goddesses are facing the head of the dead and the image is accompanied by an inscription where we read:

“They move their faces during the moan; they mourn over the secret corpse of …

Both goddesses are holding their locks swt, the water is dropping from the eyes of these goddesses…the breath comes from them (the goddesses)…”

In some moment of his resurrection the dead finds Isis and Nephtys, which leaning their faces, holding their locks of hair swt and crying over the corpse, allow the dead to breathe and revive.

There is a very similar example in the coffin of the dwarf Dyedhor, who was dancer in the Serapeum. This coffin was found in Saqqara and belongs to the Persian period. The coffin of Dyedhor shows also Isis and Nephtys pulling their frontal locks of hair (Cairo Museum, nº cat. 1294).

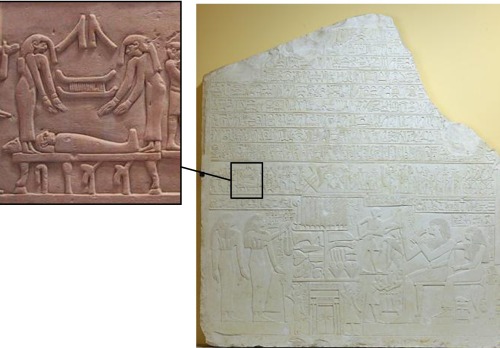

3) The stele C15 in Louvre Museum is another important document for this subject. It was found in Abydos and dates from XI Dynasty. His owner was Abkaou, chief of the cattle. In the Middle Kingdom became very popular to put a stele in Abydos in the memory of the deceased god Osiris. In this stele the lower register shows Abkaou receiving the offerings while in an upper register there is an image of the ceremonies that took place during the Osiris festivity. Two mourners are over the lying corpse and both cover their face with the hair; in fact it remembers what it is said in chapter 180 of Book of the Dead.

The inscription is much reduced: once hieroglyph tm and twice the hieroglyph nwi.

The verb tm in ancient Egyptian means “complete”, “be completed”, “join the different parts of the body” (Wb V, 303), especially when it is about the parts of the dead (Wb V, 305, 1) and nwi means “to be in charge of” (Wb II, 220); the whole could be translated as “to be in charge of completing”. In the Myth of Osiris Isis with the help of Nephtys are the ones who collect the different parts of the body of Osiris, so these two mourners of the image would also be in charge of mending the body of the dead. The nwn gesture they are doing over the body would be one of the practises for revitalizing the deceased.

Suming up, mourners in Ancient Egypt made a kind of rite with their hair during the funerals. It could be to cover the face with the hair (nwn) or pull the frontal lock of hair (nwn m). In both cases we have proofs of this practise over the corpse and always with a revitalising goal.

For understanding better the meaning of this practise we have to know more about the symbolism of hair.