Hair has been from ancient times an important element for preserving a good- looking. Recently in the blog Studia Humanitatis it was published a very interesting post about how the concept of a woman’s beauty is closely related to hair.

He mentioned a passage of The Metamorphoses of Lucius Apuleius, in which he falls in love of Fotis and concretly of her hair. The author notices then that hair is the main point of beauty of women for two reasons: 1) because it is the first thing that men see and that it is shown to them;2) becasue, if the clothes embellish the body, the hair do the same thing with the head. In fact, Apuleius dedicates a big paragraph for exalting the sensuality of a long hair, the gesture of plaiting it, the hair loose… and he says that a bald women could never be attractive. (Lucius Apuleius, The Metamorphoses, II, 8-9).

This thoutgh can also be applied to Ancient Egypt. For Egyptians the appearance was such a important thing, that cosmetic remedies were included in medical texts. For instance the Edwin Smith Papyrus includes prescriptions for renewing the skin and rejuvenating the face (Pap. Edwin Smith, V. 4, 3-8).

Hair was not an exception in Ancient Egypt among beauty cares. Egyptians were concerned, as nowadays, about grey hair and baldness. The Papyrus Ebers shows many remedies against these two problems, always using the natural components they had.

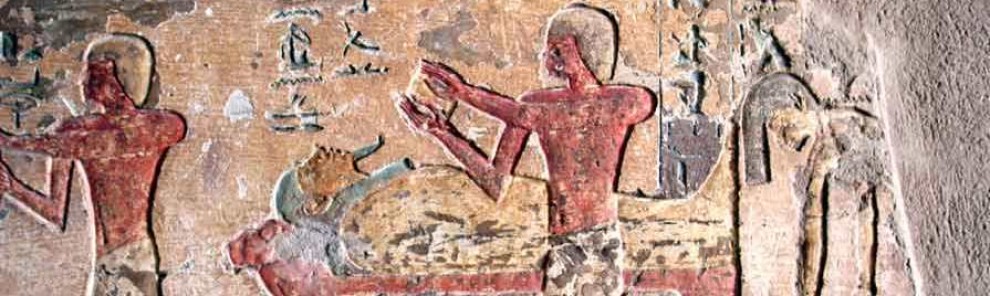

Man with sparse hair. Painting from the tomb of Horemheb. XVIII dynasty. Louvre Museum. Photo: www.lessingimages.com

For growing hair Ancient Egyptians rubbed the scalp with a mixture of tooth of ass with honey, also they rubbed the bald area with a mixture of fat from different animals (lion, hippopotamus, crocodile, cat, snake and goat).

Ancient Egyptians fought against accidental alopecia rubbing the affected area with quills of hedgehog warmed with oil or with a mixture of lead and froth of beer.

Finally, against grey hair men and women from Ancient Egypt applied blood of the gabgu bird (an unknown bird mentioned in the Coffin Texts as a dangerous bird) for dyeing the white hair, or horn of deer mixed with warm oil, or womb of cat mixed with egg of gabgu bird and oil. Grey eyebrows could be dissimulated with a mixture of liver of an ass, warm oil and opium.

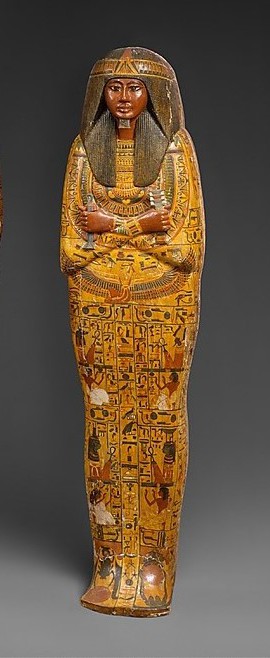

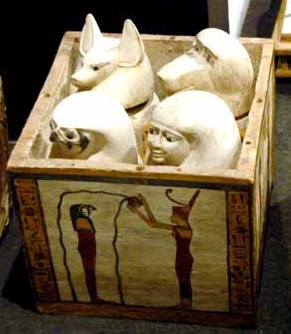

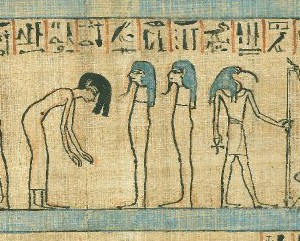

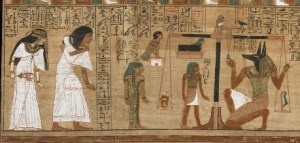

Obviously we do not know the efficacy of these beauty remedies for the hair, but our question is: if they were important in Ancient Egypt for the livings, were they also for the dead? Did the Egyptians apply these prescriptions to their mummies? Had their mummies be as beautiful as possible for the Afterlife?

That quotidian gesture of bringing the breast to the baby’s mouth is, in fact, a very basic way of opening the baby’s mouth, for allowing him to nurse. The first tip given to mothers at the beginning of the breastfeeding is to open well the baby’s mouth and to point the nipple to the middle part of the baby’s palate.

That quotidian gesture of bringing the breast to the baby’s mouth is, in fact, a very basic way of opening the baby’s mouth, for allowing him to nurse. The first tip given to mothers at the beginning of the breastfeeding is to open well the baby’s mouth and to point the nipple to the middle part of the baby’s palate.