Looking at the walls of Egyptian tombs belonging to the Old Kingdom we are aware that artists at that period of the Egyptian history represented funerary ceremony not in such an explicit way as they did later on. The mastaba of Qar is a good example of it; in the north wall of court C there is a scene of the funerary procession where we can perfectly see all the personnel taking part in the ceremony, but whose role is not always too clear. We can see the two mourners Drty (the professional mourners) with short hair accompanying the coffin, the wt priest (embalmer), the Xr-Hb (lector priest) and the rest of the funerary staff. But do we really know what are they doing?

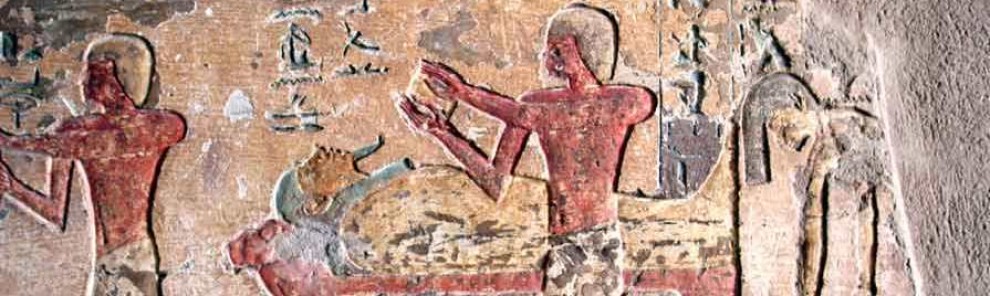

Scene of the funerary procession in the tomb of Qar. V-VI Dynasty. Giza. Image from W. K. Sympson.

I just would like to focus on one small scene of the whole composition where one Drt (“kite”) without mane appears with the wt priest or embalmer. Both are facing each other and uttering some words; behind the embalmer stands the lector-priest. An altar with food offers stands between them and the inscription over there says: “D3t r3”. Looking at their gesture (the hand on the mouth) we could suppose that it is just describing it. But, makes that sense?

Detail of the relief in the tomb of Qar. The lector priest, the embalmer and the mourner Drt in the funerary ceremony for the deceased. V-VI Dynasty. Giza.

The expression D3t r3 was also used in Ancient Egypt for referring to feeding[i]. It was the way of expressing the fact of taking the mouth to the food, as when the mother takes the baby to her breast for nursing him. Taking into account that the inscription is over the altar with food, it could be more logical to think of this meaning. So, they both would be feeding (and therefore giving life) to the dead.

But that is not all, what elements do we have for interpreting the scene in a more conscious way?

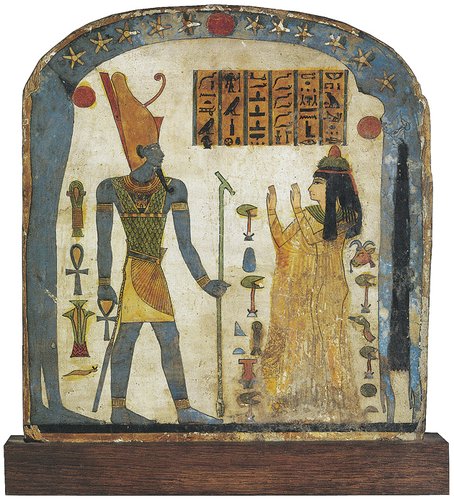

1) The scene happens during the funerary ceremony, so the first personage we have to think of is the deceased. And we already know that in the Ancient Egypt belief he was considered as a new born. The rebirth was a new birth, so the mummy became a foetus in the womb and he came back to life after the whole gestation. After that his first food would be the breast milk. In this context the expression D3t r3 would be full of meaning.

2) We see the presence of a Drt mourner, which played the role of Isis. In later Egyptian documents, it is more usual to find two Drty, as the representatives of Isis and Nephtys. Both played a very important role making a special mourning ritual; in it both shook and pulled their hairs reviving again the episode of the myth of Osiris in which the corpse of the god was revived by Isis. She put herself as a kite over her husband’s phallus and gave him back his virility. It is very important to notice in the image her short hair, since, according to our research, we consider that, after the mourning ritual, her hair was cut. So, for the Egyptian artist to represent these mourners with the short hair was the way to indicating that they were not common mourners, but the representatives of Isis and Nephtys and the women taking part in the deceased’s resurrection.

3) The embalmer (wt) is very present during the funerary procession. The embalmer was the responsible of the mummification and in the myth of Osiris this was the role of Anubis. Once every limb from the god’s body were collected, Anubis recovered the mummy assembling each member, afterwards Isis with her magic recovered all vital faculties and Osiris came back to life.

4) The lector priest was always present in Ancient Egypt funerals reciting all sacred texts and leading the ceremony. In the Qar’s tomb he is the third member of the staff officiating during the rite.

So, at first sight we can assure that this small scene is indicating a ritual made for the mummy’s restoration. But we can go on farther.

Closing the register we find the image of two tied[ii] oxen. It seems quite logical to think about just one, alive in the upper half and already dead in the lower one. The slaughter of an ox is a practice made in all funerals. It was connected with the sacrifice of the sethian victim and this rite was a reproduction of the dead of Seth in the myth of Osiris.

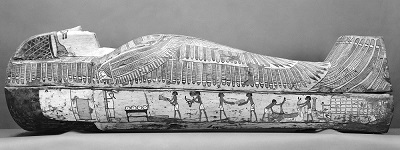

Funerary practice in the mastaba of Qar with lector priest, embalmer and mourner Drt; the scene is closed by two images of an ox. V-VI Dynasty. Giza. Image: W.K. Sympson.

All components of this scene refer to practices made mythically for restoring the corpse of Osiris, giving him back to life and avenging his death; and everything supervised by the lector priest. All that is what happened in the Opening of the Mouth ceremony, the main Ancient Egypt rite for granting the resurrection of the dead.

Summing up, this small scene was very important in the decorative program of Qar’s tomb, it had to be there for assuring the Qar’s resurrection in the Afterlife. But the Egyptian artist in the Old Kingdom had to find the way of representing it in a discrete (even codified) way.

[ii] As it is indicated in the hieroglyphs