Two mourners in the new discovered tomb of the Egyptian King Senebkay?

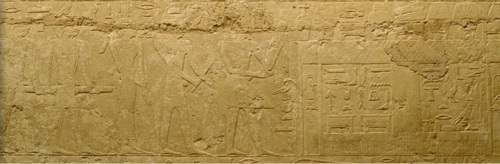

That was my first thought when I saw yesterday the new about the recent discovery of the university of Pennsylvania in Abydos. The tomb of King Senebkay, probably dating from XIII Dynasty, built in a simple way and, according to archaeologists, with reutilised blocks, is not too well preserved.

The painted decoration that it remains in this Ancient Egypt grave is very scarce and also quite simple. On a white background some images are visible, like the King’s cartouche, the winged sun disk and some female figures.

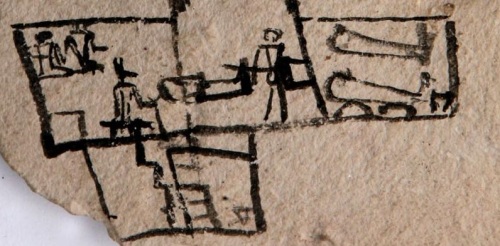

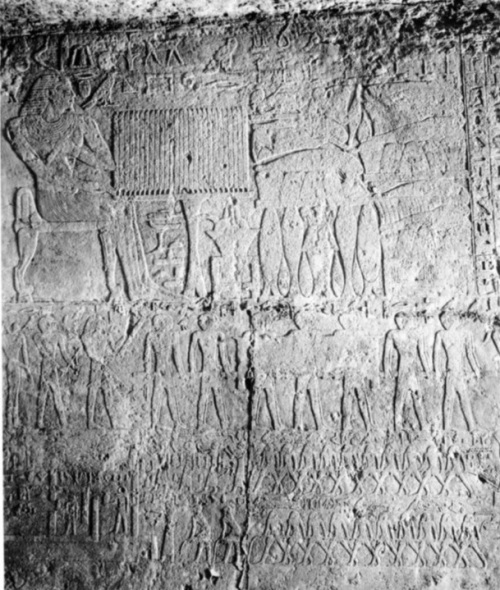

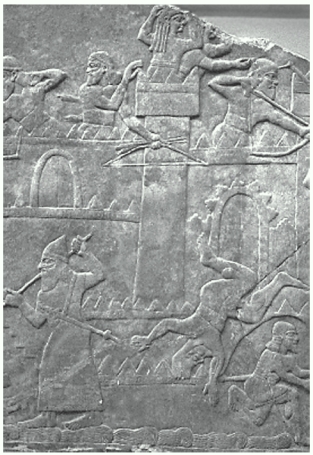

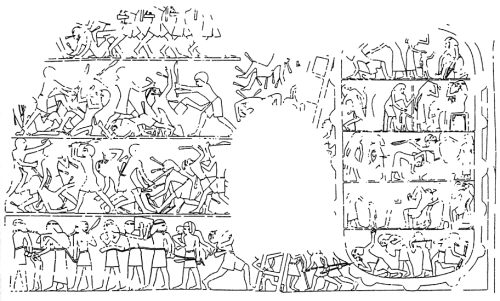

The scene which attracted our attention was the one at the last chamber. It is very typical Egyptian funerary scene. On the top of the wall a winged sun disk (image of Horus) is over a painted false door, which is crowned by the heker frieze and contains two Udjat eyes. This icon is very common in Middle Kingdom coffins; the eyes, in the Ancient Egypt belief are the deceased’s connection with the world of the living, so this part of the tomb symbolises the limit between this world and the Hereafter. At both sides of the false door two standing women appear as the only human beings.

According to Joseph Wagner (responsible of the works), the bad conditions of the tomb could be a proof of the bad economical situation of Egypt at that period (Second Intermediate Period). If so, it would make sense the lacking decoration of the tomb (let’s remember that itis about a Pharaoh’s tomb). But this premise would be important. If the decorative programm was limited, the artists had to include in the tomb just the essential for granting the Senebkay’s resurrection. Obviously, the false door and the Udjat eyes as the meeting point between the world of the living and the Hereafter were necessary. And what about those two women?

Let’s emphasize some points:

These two women appear alone, with no other human figures, so they were important.

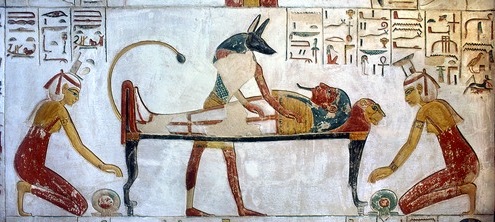

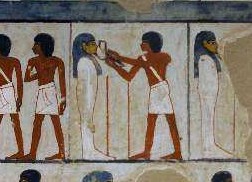

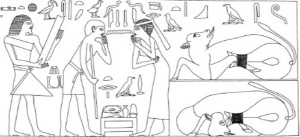

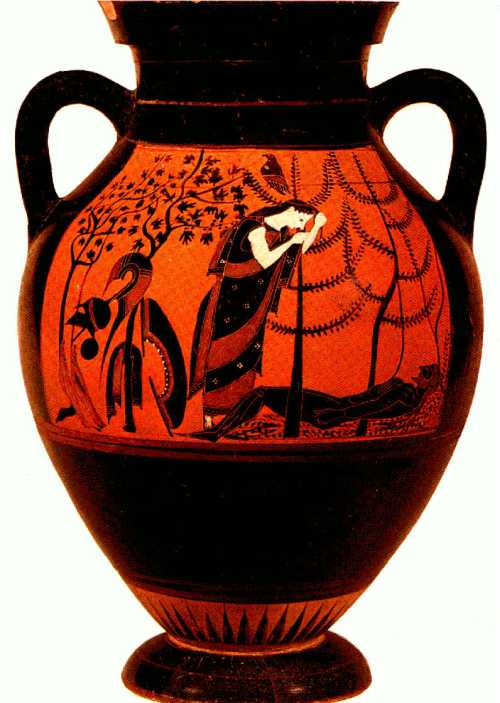

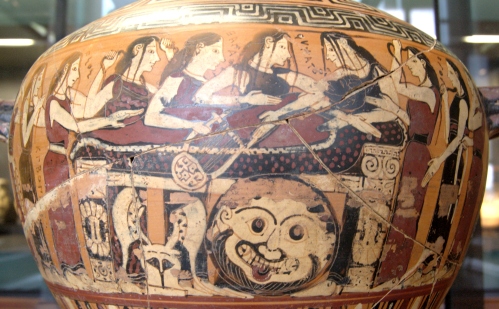

These two women stand at both sides of the false door, in the same way Isis and Nepthys stand later on at both extremes of the coffin and/or the mummy.

These two women are at the connection point between the world of the living and the Hereafter. It is the place were the Egyptian mummy comes back to life after the resurrection ritual. We have seen all along our research that the two mourners in the role of Isis and Nephtys were a very important part in the resurrection of the deceased.

These two women wear around their wrists apparently the hieroglyph of the seal. We still do not know really how to interpret that, but at first sight one image came to mind: the one of Isis and Nephtys in the New Kingdom scenes at both extremes of the coffin holding the shen ring, as a symbol of eternity. The seal and the shen ring hieroglyphs could be both determinative for the Egyptian word djebat (Wb V, p. 566), which meant “signet-ring“, so the seal in a ring worn by the Pharaoh.

These two women had to be there for granting the resurrection of the king. The question is who were they? There is an inscription next to them, which probably will shed light on that issue. Meanwhile let’s also think that the tomb is located in Abydos, place were the Myth of Osiris was specially important. Had the Egyptian artist represented the Osiris (so Senebkay) resurrection as summarized (or even cheap) as he could?