Ancient Egypt language had many different words for expressing the disorder in a long female hair.

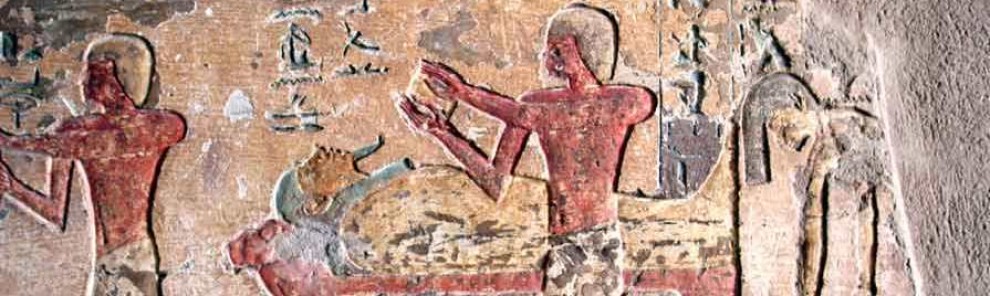

We have seen that in the funerary context the most used one was the verb nwn, which literally meant “to dishevel the hair over the face”,![]() that is, to shake the mane of hair forwards and cover the face with it. So the verb refers to the fact of extending the hair upside down. That was the gesture the mourners did during their mourning ritual in the Egyptian funerals. The verb is documented already from the Old Kingdom and closely realted to the funerary context.

that is, to shake the mane of hair forwards and cover the face with it. So the verb refers to the fact of extending the hair upside down. That was the gesture the mourners did during their mourning ritual in the Egyptian funerals. The verb is documented already from the Old Kingdom and closely realted to the funerary context.

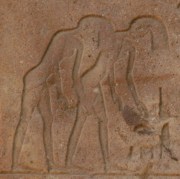

All during this blog we have seen how the nwn gesture was made by the common mourners during the cortège, but overall by the two professional mourners in the role of Isis and Nephtys during the resurrectional rites. Making the nwn gesture those two women evoked some crucial moments of the Myth of Osiris, as the copulation beweet Isis and Osiris, when Isis as a kte produces vital breath with her wings or the maternity of Osiris.

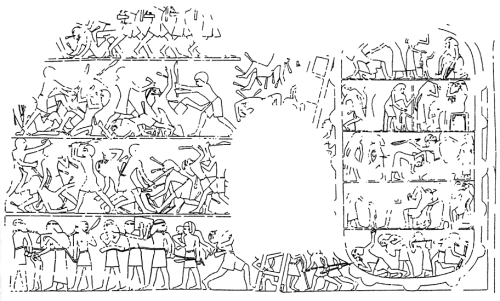

Another Egyptian word was tejtej (also written with the determinative of hair) ![]() which meant the tangled hair. According to Erman and Grapow, it was documented from Middle Kingdom and the sense of this verb was related to disorder. It was also applied to the fact of having the ideas mixed-up, so producing a state of confusion. The enemies of Egypt were as well tejtej when captured, since they were put all together in a disordered pile.

which meant the tangled hair. According to Erman and Grapow, it was documented from Middle Kingdom and the sense of this verb was related to disorder. It was also applied to the fact of having the ideas mixed-up, so producing a state of confusion. The enemies of Egypt were as well tejtej when captured, since they were put all together in a disordered pile.

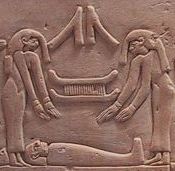

Isis as a kite over the corpse of Osiris. Relief from the temple of Seti I in Abydos. XIX Dynasty.

It is interesting to notice that chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead, which relates the copulation of Isis with Osiris, uses the verb tejtej for referring to the disordered hair of isis during her copulation with Osiris (Urk. V, 87). It still gains sense when we realise that tejtej is a reduplicated form from the Egyptian verb tej, which meant “get drunk”. And one epithet of Isis from the New Kingdom was “Lady of the Inebriation”. So, aluding to this state of confusion, which in the Myth of Osiris would be the moment of the copulation.

The verb sps has a very similar meaning as nwn, it was used for the tousled hair![]() , the main difference is that sps was documented from the New Kingdom, concretely in the Book of the Dead, while nwn is an existing verb for disheveled hair from the Old Kingdom. On the other hand it seems quite sure that nwn was the verb for referring to the concrete gesture of covering the face with the hair.

, the main difference is that sps was documented from the New Kingdom, concretely in the Book of the Dead, while nwn is an existing verb for disheveled hair from the Old Kingdom. On the other hand it seems quite sure that nwn was the verb for referring to the concrete gesture of covering the face with the hair.

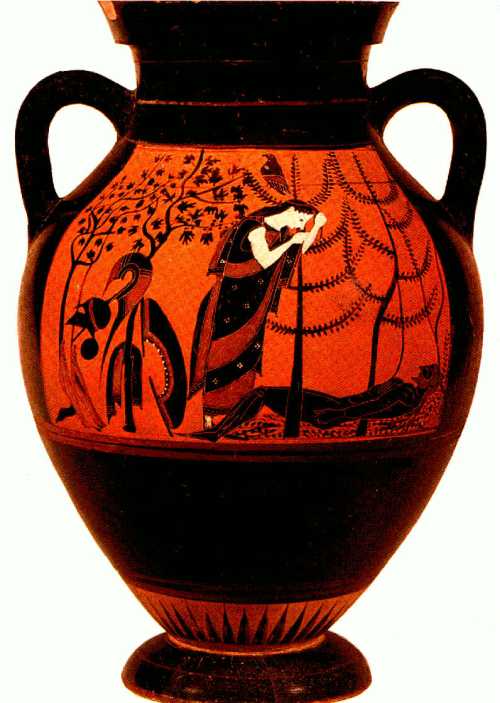

Two women shaking their hairs in the Festival of the Valley. Relief from the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut in Karnak. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín

We have also to notice that the verb sps was later on also written with the determinative of a dancing person and it meant “dance”. ![]()

At that point we could think that the verb sps could refer to the tousled during some dancing. If so, it comes tour mind those dances made by women during the Festival of the Valley or the Heb Sed. In them those dancers shook their hair forwards and disheveled it on her faces as symbol of renewing.

For the moment we cannot give many conclusions, but we know that the original word related to disheveled hair was nwn, as the gesture of shaking hair forwards by the mourners in the funerary ceremony.

In the Middle Kingdom appears the verb txtx, apparently evoking the chaos and disorder of a tousled hair and applied to the copulation of Isis and Osiris.

From the New Kingdom the verb sps is another way of referring to disheveled hair, although probably taken from ritual dances in which the dancing women made the nwn gesture of shaking hair forwards.