We have seen Egyptian mourners, with Egyptian tears, shaking and pulling Egyptian hair and crying for an Egyptian corpse. But crying is spontaneous human expression, so mourning is not an isolated Egyptian practise; it is also a common behaviour in many other cultures, even nowadays it is still an important way of expressing desperation and sadness in case of death or any kind of disaster.

We have tried to look for similar examples of mourning in some other cultures near Egypt and more or less contemporary. We have found in some cases some coincidences, but also big differences.

In many African areas, women mourn in the same way Egyptian women did. They scream, lie down on the ground, and tear their clothes. But, apparently nothing is done with the hair.

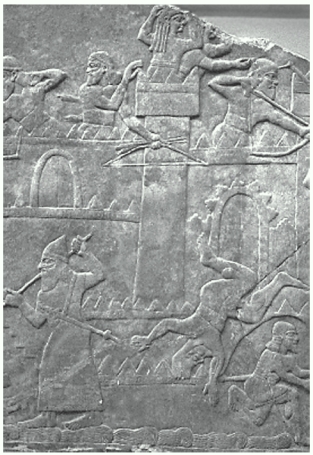

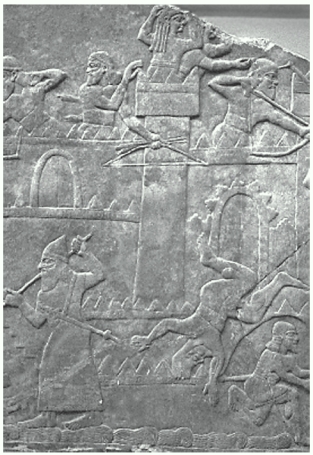

Mourning woman when te city is being besieged. Relief from the tempel of Ashurnasirpal II in Nimrud. IX BC. Photo: http://www.lectio.unibe.ch

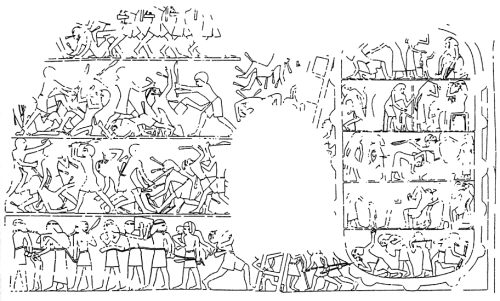

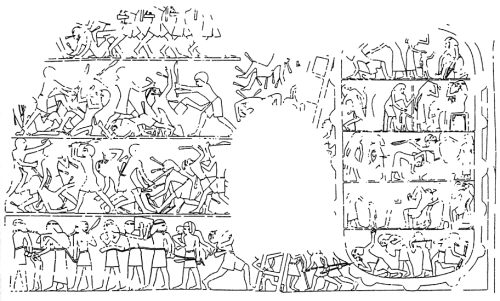

From the reign of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC) in Assyria come some examples of women mourning and making gestures similar to those one we found in Egyptian funerals. His son Salmanasar III also left similar iconography. They are women crying desperate because their city is being attacked and their men killed. The document remembers the scene coming from the tomb of Inti in Dishasha (near Bahr el-Yusuf) from the IV Dynasty, where a woman is pulling her front lock of hair desperate because the city is being besieged.

Drawing of the relief in the tomb of Inti. Inside the fortress we can see the major and a woman, both pulling their lock of hair. Dishasha. VI Dynasty.

But although they are examples of desperation as those Egyptian ones, the Assyrian women do not pull their hair nor shake it forwards. When Assyria was ruled by Ashurnasipal II and Salmansar III Egypt was in its Third intermediate Period.

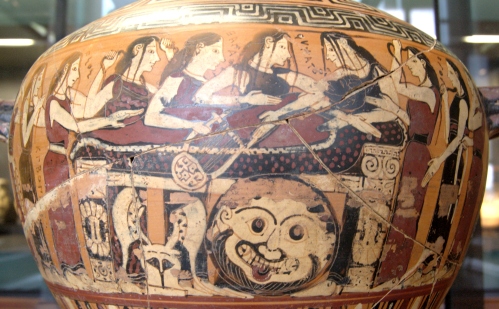

There are several documents from the Archaic Greece showing women mourning in funerals. Many funerary plaques from that period show these women moaning and pulling locks of hair from their heads. Loutrophoros were vessels of pottery for water used in funerals, they were decorated with funerary images, and many of them show female during the mourning pulling locks of hair.

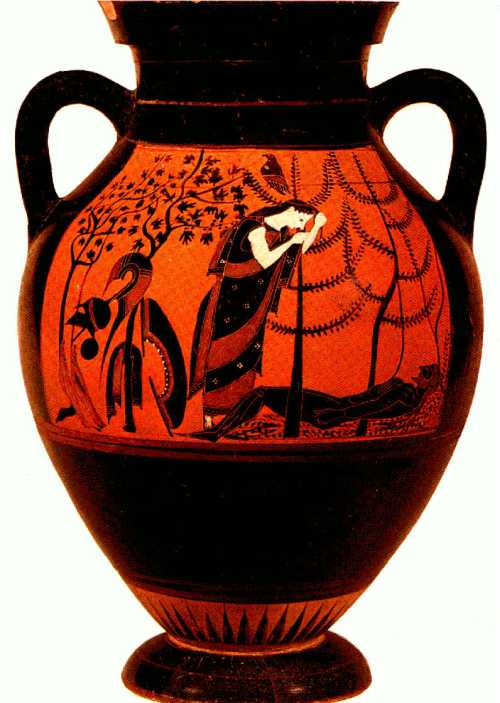

In an amphora in the Etruscan Museum in Vatican the goddess Eos is depicted mourning the death of her son Memnon at the hands of Achilles, she is bended over her son’s corpse pulling a front lock of hair. Another good example for us is a hydria from the VI century b. C. containing the mythological scene of the mourning of Achilles killed by Paris; some of the Nereids appear pulling locks of hair. While that was happening in Greece, Egypt was ruled by the XXVI Dynasty.

Greek Illiad describes how in Patroklos’ burial his fellows cut themselves locks of hair and covered his body with them and how Achilles cut a yellow lock of his hair and put it in the hands of Patroklos. These two gestures were made in honour of Patroklos, but not for helping him in a final resurrection. Anyway, did this practice belong to Homer’s times (VIII century BC) or to the Trojan War’s times (usually dated in XII century BC)? If we consider the first date Egypt is in the Third Intermediate Period, while the second one coincides with the end of the XX Dynasty.

As we can see all the Egyptian proves are much more ancient, some of them more than 2.000 years. On the other hand, in Ancient Egypt there were two types of mourning, the secular one and the ritual one. The first one is closer to the foreign examples we have seen: a human behaviour for sadness or in honour of the death. In the second case the gestures belong to a rite, which comes from a myth. Egyptian mourners during the Opening of the Mouth ceremony made the mourning ritual with their hair for reviving the mummy. Does anybody know something similar in other cultures?