In the former post we have seen mainly those interesting references taken from chapters of the Coffin Texts. However they are not the only documents where we can find the proof of the importance of the mourner’s hair in the funerary ceremony of Ancient Egypt. Reliefs and paintings show us how mourners effectively pulled and shook their hairs in the funeral.

Old Kingdom.

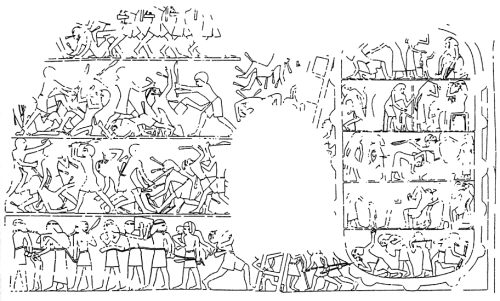

Thanks to the Pyramid Texts we also know that the gesture of covering the face with the hair existed already in the Old Kingdom. Some tombs of that period offer us scenes with mourning women pulling their lock of hair (nwn m). The tomb of Mereruka in Saqqara and the tomb of Idu in Guiza, both from VI Dynasty, have reliefs of mourning women some of them are just crying, rocking, beating their arms and heads, but we can see some women pulling their front lock of hair.

Relief of mourners, one of them pulling her front lock of hair. Tomb of Mereruka in Saqqara. VI Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

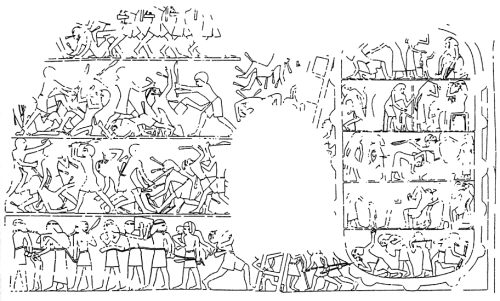

Drawing of mourning women. Tomb of Idu in Guiza. VI Dynasty.

I want to emphasize in the tomb of Idu two reliefs representing mourning men who are also pulling their hair. It is not so usual to find scenes of mourning men in Ancient Egypt funerals and less shaking their hair or pulling from it. Here there is another open subject for a future research.

This same gesture we find it in the tomb of Inti in Dishasha (near Bahr el-Yusuf) from the VI Dynasty. In this case we are not in a funerary scene, but a war moment, in it the major of the city and a woman in front of him are pulling their front lock of hair. Although it is not a mourning scene, the gesture happens in a moment of desperation and suffering, the same feelings had to show mourners in funerals.

Drawing of the relief in the tomb of Inti. Inside the fortress we can see the major and a woman, both pulling their lock of hair. Dishasha. VI Dynasty.

Middle Kingdom.

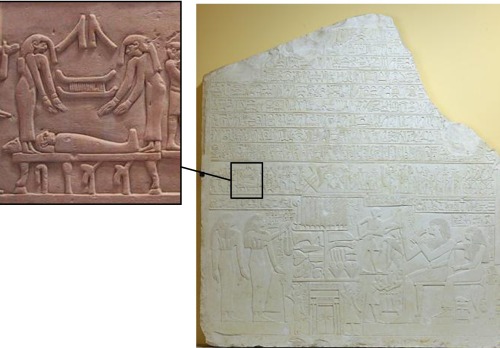

The stele of Abkaou from Abydos in the Louvre Museum dates from the XI Dynasty and it is one of the best documents for us coming from the Middle Kingdom. In it the artist represented the ceremonies of the Osiris festivity, one of the scenes shows two women shaking hair forwards the mummy.

From Middle Kingdom comes a fragment of a coffin found in Abydos with rests of painting on one side. It shows a funerary procession where a mourning woman with tears falling on her cheek is bent and with the hair over her face. It seems that she would walk mourning besides the coffin, which would be carried by some men.

Mourning woman beside the coffin. Image in a coffin of the Middle Kingdom from Abydos.

New Kingdom.

The main part of the figurative examples comes from the New Kingdom:

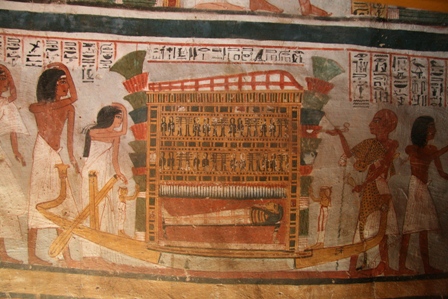

The tomb of Amenemhat (TT82) in Gourna, dates from the XVIII Dynasty and over the door there is scene in which the mummy of Amenemhat lies on a canopy, a priest in front of the dead is making a libation and burning incense; four mourning women are crying for the deceased and two of them are making the nwn gesture of shaking their hairs and covering their faces with it.

Drawing of the relief from the tomb of Amenemhat (TT 82) in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty.

A very similar scene is on the tomb of Ineni (TT81), also in Gourna and also from XVIII Dynasty. In front of a group of mourners there is one with the body bent, although the head is not preserved it is obvious that this woman was making the nwn gesture.

The same scene is in the tomb of Minnakht (TT87), also in Gourna and also dating from XVIII Dynasty. The only difference here is that she is making the nwn gesture and facing the rest of mourners.

The tomb of Renni in el-Kab dates from the reign of Amenhotep I and it is very noticeable how a mourning woman is making the nwn gesture just in front of the dead.

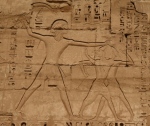

A very similar scene is still visible in a relief in the funerary temple of Seti I in Dra Abu el-Naga, where both mourners are making the gesture nwn on both extremes of the body of the dead pharaoh.

The tomb of Rekhmire in Gourna (TT100) shows to us also an image of mourning in the north wall of the corridor, in which a group of women are mourning, two of them making the nwn gesture. According to the whole scene, this could be happening while inside the tomb or inside a construction was taking place the ceremony of the Opening of the Mouth. But there is something that makes this image different from the rest we have seen: a totally lack of dynamism. While in the former examples women shake their hair forward with energy and with signs of movement, Rekhmire’s mourners have the body straight and their arms are crossed over their chests, showing a passive attitude.

Mourning women in the tomb of Rekhmire. Gourna, XVIII Dynasty. Photo. Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín

This stillness and the fact that it maybe could be happening apart from the Opening of the Mouth, could make us think that, while in some place are taking place the practises for the resurrection of the dead, in other place these mourners would be making the nwn gesture with a negative connotation, I mean, like a real exhibition of pain and sadness that dives the mourner in the darkness of the chaos that brings about the death.

Texts and iconography show that mourners made two gestures: nwn m (pull the front lock of hair) and nwn (shake hair and cover the face).

In which moment of the funerary ceremony would take place this nwn m/nwn gesture? According to Davies and Gardiner, it could happen some when between the embalming rites and the final celebrations of the funeral.

We will treat that point later. Before we need to know why the hair became such an important element in the funerary rite.