Due to the estrict rules of the Egyptian art, artists in Ancient Egypt needed to find unnatural ways of expressing some movements, especially during the Old and Middle Kingdom. Distorsion and sprain characterises dynamic scenes (dancing, acrobaces, games…) in those periods of Egyptian history.

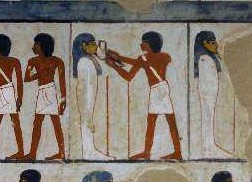

Dancing scene from mastaba of Mereruka. VI Dynasty. Saqqara. Image: http://www.osirisnet.net

Musician girl playing the long neck lute. Tomb of Rekhmire in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty. Photo courtesy: Dagmar Krejci.

However, from the New Kingdom dynamism appears in Ancient Egypt decoration in a more natural way. The Egyptian artist gradually tretaed the bodies in movement in a less rigid way. And one of the elements which helped them was the hair. We have already seen, for instance, that hair was a resource for expressing the movement while playing an instrument. However, hair as an artistic resource of Egyptian artist applied to the body language dates not from the New Kingdom, but before. According to the iconography, the mourning gesture of shaking hair forwards was expressed in Ancient Egypt by drawing the mane of hair over the woman’s face. That way, the Egyptian artist represented this body movement. We can imagine that the mourner was not permanent bended, but moving her body and head forwards and backwards.

Detail of the stele of Abkaou in the Louvre Museum. XI Dynasty. Photo: http://www.commons.wikimedia.org

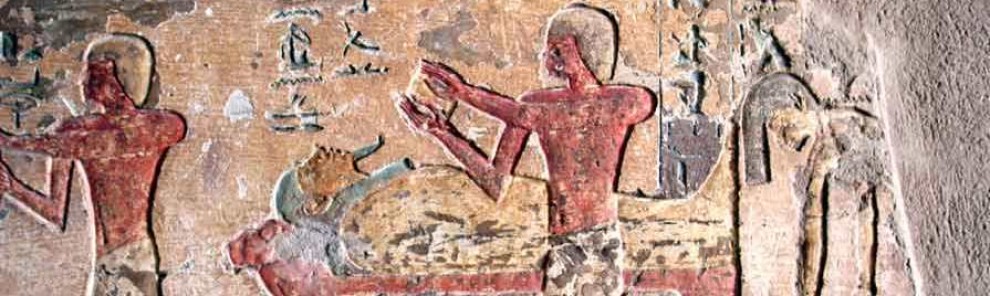

As long as we know, the first example of this artistic resource comes from Middle Kingdom; in the stele of Abkaou (XI Dynasty) and in a fragment of a coffin (XII Dynasty) mourners bend their body and their hair is forward.

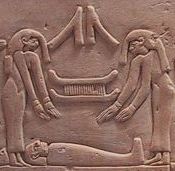

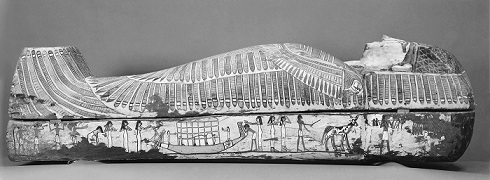

Later on, in a rishi coffin from XVII Dynasty, there is a scene of the funerary procession, in which one mourner bends her body and shakes the hair forwards. That way of expressing this mourning gesture will go on in the Ancient Egypt iconography.

Rishi coffin. Right side with the funerary procession. On the left a common mourner shaking hair forwards. XVII-XVIII Dynasty. Thebes. Photo: http://www.metmuseum.org

Tomb of the Dancers from Thebes. XVII Dynasty. Ashmolean Museum of Art and Achaeology in Oxford. Photo: www.ashmoleanprints.com

The paintings from the “Tomb of the Dancers” date from the XVII Dynasty and we can see in them how in that period of the Egyptian history artists started to treat the body in movement in a more realistic way, traying to express what that women were doing: jumps, gestures with the shoulders, arms raised…, although their hair are motionless.

In the New Kingdom, Egyptian art takes the technique from the sacred funerary decoration and the hair forwards and/or backwards became a way of drawing more daily gestures. Artist will learn to manipulate hair in a realistic way for expressing the movement of dancing.

Music scene from the tomb of Djeserkaraseneb. XVIII Dynasty. Tempera of Charles. K. Wilkinson. Photo: www.metmuseum.org

In the tomb of Dyeserkaraseneb (TT 38), dating from the reign of Tuthmosis IV there is a music scene in which one of the musicians appears with her plaits moving for expressing how she turns he head back. Next to her a dancing girl is slightly bended backwards, whose lateral plaits of hair were drawn following her movement.

Dancing girl. Tomb of Dyeserkaraseneb (TT 38). XVIII Dynasty. Photo: www.osirisnet.net

Dancers and musicians from the tomb of Nebamon (TT 90). XVIII Dynasty. Photo: www.commons.wikimedia.org

The famous scene of the dancers from the tomb of Nebamon (TT 90) shows one of the dacing girls with both laterals plaits of hair shaing forwards with her head. In fact, the whole body was treated in such a realistic way that we can imagine her moving herself to the rhythm of the music her fellows are playing.

In that period of Egyptian history the artists learnt how to draw the body movement in a more realistic way manipulating many parts of the human body, included the hair. This last one was a technique taken from the sacred funerary art of Ancient Egypt.

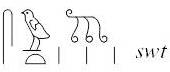

It also appears in the New Kingdom and it seems to refer concretly to “plaited lock of hair“. It is very interesting to notice the between “nebed” and “nebedj”.

It also appears in the New Kingdom and it seems to refer concretly to “plaited lock of hair“. It is very interesting to notice the between “nebed” and “nebedj”.  This last word exists in Ancient Egypt from the Old Kingdom and its translation was “the bad“, in fact with the hair determinative it could also have the enemy determinative. There also was the proper noun of “Nebedj“, which was a way of naming Seth, the enemy of Osiris (and also Apophis,the enemy of Re).

This last word exists in Ancient Egypt from the Old Kingdom and its translation was “the bad“, in fact with the hair determinative it could also have the enemy determinative. There also was the proper noun of “Nebedj“, which was a way of naming Seth, the enemy of Osiris (and also Apophis,the enemy of Re).