Last week we saw that in some cases Egyptian art offers images, whose meaning seems not clear, but which are based on well known practices from Ancient Egypt.

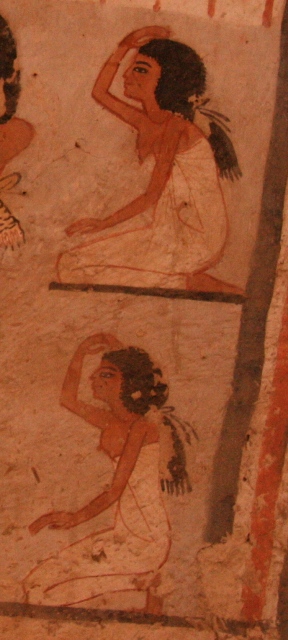

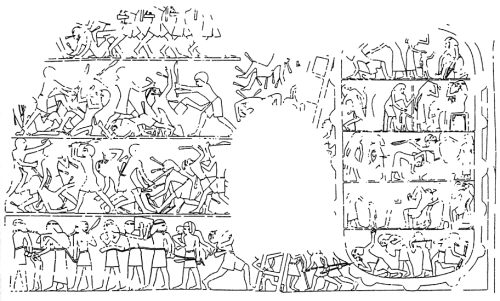

That was the case of two scenes, one from the Book of the Caverns in the tomb of Ramses IX and the other one from the temple of Osiris in Abydos. In both cases four mourning women appear pulling and shaking a front lock of hair.

Four mourners for Osiris with their front lock of hair falling forwards. Temple of Abydos. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín

We know that in Ancient Egypt belief the official mourners who took part in the deceased’s resurrection were two, Isis and Nephtys. However in these two images they are four women making a mourning rite. Can we deduce something more about the identity of this foursome?

These four female figures are categorized in the tomb of Ramses IX as “goddesses” and they are included in the decorative program of a tomb and the temple of Osiris in Abydos, both belonging to a funerary context. So, for deducing more about them, we have to consider three main aspects: They are four, they have a divinie nature and they are related to the mummy and the body’s restoration.

Is there a group of four goddesses in Ancient Egypt, who took care of the deceased? Yes, Isis, Nephtys, Neith and Serket. In the Egyptian thought they four formed a team for protecting the dead, or more concreetly, the organs of the dead.

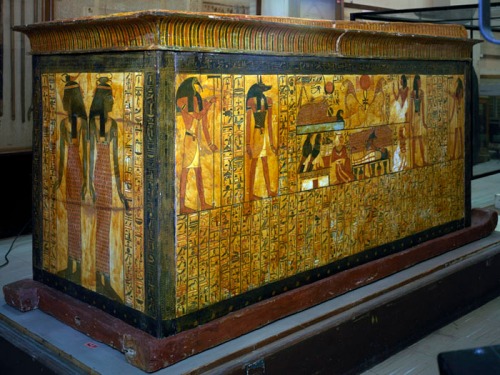

Canopic shrine of Tutankhamun with Serket on the left and Isis on the right. XVIII Dynasty. Cairo Museum. Photo: www.globalegyptianmuseum.org

For that reason they four were the guardians of the caponic jars which contained the organs of the dead and of the coffin, which contained the mummy. And their image together were usual in these Egyptian canopic chests and sarcophagi.

Coffin of Khonsu, Sennedjem’s son, from Deir el-Medina. Neith and Serket at the feet end. XIX Dynasty. Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Photo: www.drhawass.com

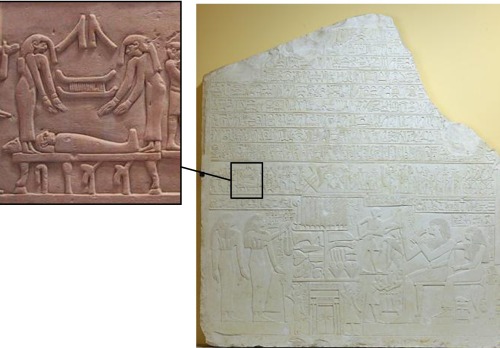

These are the four goddesses who spread their arms over the funeral chest of Tutankhamun. We can see them also in the coffin of Khnonsu (Sennedjem’s son) from XIX Dynasty, Isis and Nephtys are depicted at the head end of the coffin, while Neith and Serket appear together at the feet end.

Coffin of Khnum Nakht. Feet extreme with inscriptions referring to Nephtysand also Serket. XIII Dynasty. Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York.

Neith and Serket, together with Isis and Nephtys, were also mentioned in the inscriptions of some coffins and in canopic chests dating from the Middle Kingdom.

Wooden canopic chest of Satipi. Neith is included in the inscription. XII Dynasty. Photo: British Museum.

So, the union of these four goddesses was something well established in Ancient Egyptian belief. And the four mourners in the tomb of Ramses IX and the temple of Osiris in Abydos could perfectly be those ones.