We know that goddess Nut places Isis and Nephtys in some Egyptian coffins of the XII Dynasty. That goddess, as mother of these two mourners, decided to put Isis at the feet and Nephtys at the head of the mummy.

But that was not always like that in the Egyptian belief.

Some other coffins from XII dynasty and also found in Middle Egypt show that some other gods of the Heliopolitan cosmogony were also involved in that decision.

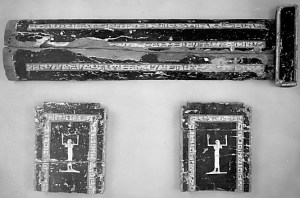

Feet end of inner coffin of Gua from el-Bersha. XII Dynasty. Photo: www.britishmuseum.org

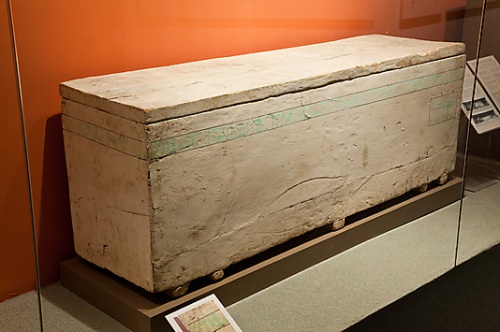

The inner coffin of Gua, from el-Bersha, presents inscriptions at both extremes of the box. At the feet end we read “Words said by Geb, I have put Isis at your feet in order she weeps you“. At the head end the hieroglyphs show that again Nut is the responsible of placing Nephtys there.

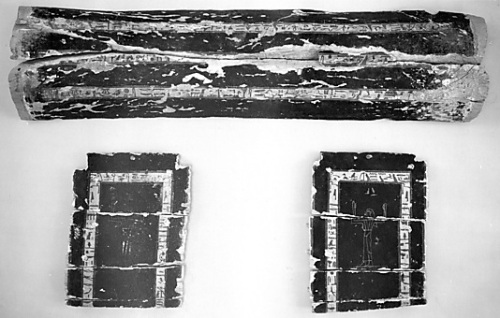

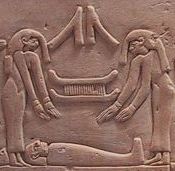

Head end of the coffin of Nakhti from Asyut. XII Dynasty. Photo: www.cartelfr.louvre.fr

The coffin of Nakhti from Asyut is different. At the head end of the box we read: “Words said by Ra, I have put Isis at your head in order she weps you and she mourns“.

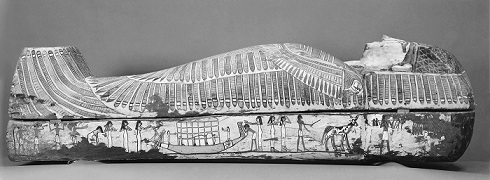

Feet end of the coffin of Nakhti from Asyut. XII Dynasty. Photo: www.cartelfr.louvre.fr

At the feet end we read: “Words said by Ra, I have put Nephtys at your feet in order she weps you and she mourns“.

In the coffin of Nakhti we find two things. On one hand Isis is at the head, while Nephtys is at the feet; the opposite of the expected location. On the other hand, the one who decides that location is Ra, the main god of the Heliopolitan cosmogony.

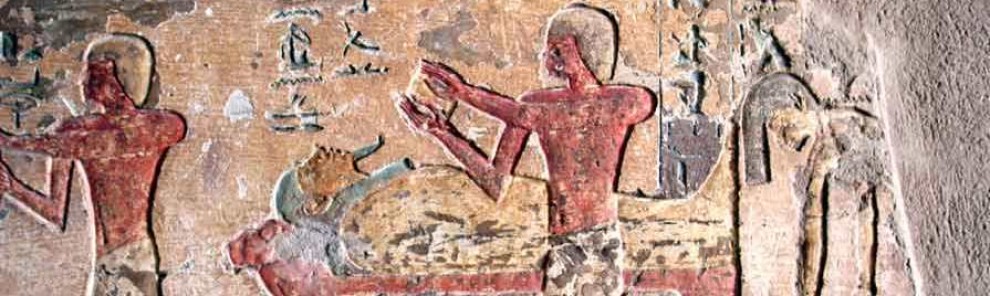

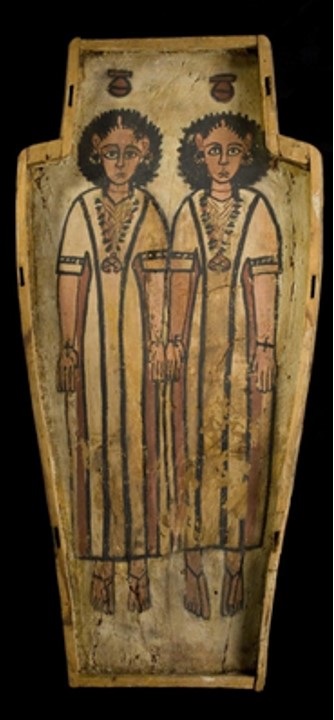

The coffin of Sebekhetepi from Beni Hassan has no trace of Isis andNephtys at both ends of the box. Instead of that, Sebekhetepi is in front of Anubis and The Great God Lord of the Sky, which is usually an epithet of Re.

These three coffins date from the XII Dynasty and come from Middle Egypt. The information we get from the inscriptions demonstrates that nothing about this subject was still fixed in the period of the Egyptian history.

Some reflections come to my mind:

- The Egyptian mourning rite for helping in the dad resurrection was still too unknown and also the role of these two women as representatives of Isis and Nephtys. So what they did or where the were was not so clear for Egyptian artists.

- The mourning rite had a deep osiriac origin and was not yet well stablished in Egyptian decoration.

- The mourning rite and its osiriac origin needed the Heliopolitan cosmogony for helping in that stablishment. Maybe Egyptian priests during the Middle Kingdom were atill looking for the way of combining these two traditions in the Egyptian coffins.