The Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom have four speeches mentioning how the female shake their hair for the deceased:

CT 66, CT 99, CT 167 and CT 674.

In chapter CT 66, where we can read:

”…Isis is nursing you; Nephtys gives her breast facing down.

The Two Ladies of Dep (Pe and Dep were the city of Buto in Lower Egypt) give you their hairs…”

It is interesting to notice how the word for “The Two Ladies” can be written also with the determinative of disheveled person: ![]()

![]() This hieroglyhp is a determinative in the verbs nwn (also wnwn) or sps, which mean « to mess one’s hair up or cover the face with the hair as sign of mourning ». Mourning women made this gesture, while men usually let their beard and hair grow up for some days (Desroches-Noblecourt, 1947, p. 230) and still the fellahs were doing that last century (Blackman, 1948, p. 58).

This hieroglyhp is a determinative in the verbs nwn (also wnwn) or sps, which mean « to mess one’s hair up or cover the face with the hair as sign of mourning ». Mourning women made this gesture, while men usually let their beard and hair grow up for some days (Desroches-Noblecourt, 1947, p. 230) and still the fellahs were doing that last century (Blackman, 1948, p. 58).

Is is very usual to see in the scenes of funeral procession women making special gestures as a sign of mourning. In the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom we can read:

« The souls of Buto rock for you; they beat their bodies and their arms for you,

They pull their hair for you… » (Pyr.1005, 1974)

And going on forward, we find the same expression in the chapter 180 of Book of the Dead of the New Kingdom:

“…mourners have disheveled for you (or over you),

they beat with their arms for you,

they scream for you,

the cry for you… » (BD, 180)

Both, words and determinatives, recall those funerary scenes in chapter 168 of Book of the Dead. The texts happens during a procession in which the « gods of the Beyond are following Re-Osiris and among them are the « Mourners of Re».

Papyrus of Muthetepti with mourning women in the cortège of Re. British Museum. XXI Dynasty. Photo: http://www.britishmuseum.org

In the chapter 66 of the Coffin Texts we find two actions together: giving the hair and nursing the dead. During the funerary procession in Ancient Egypt was very common to pour some milk in the way the coffin was passing by. This had a strong symbolic meaning; because the milk is the first nourishment of a child and it is transmitted by his mother, so this gesture is like a resurrection act. Isis brings to live the deceased and the death becomes a new birth. And that happens when Isis and Nephtys present their hairs sema. In fact, thinking of the lying body of dead, could we also consider the expression “give the hair” as a metaphor of “bending over him”?

In the chapter 991 the dead is assimilated with the god crocodile Sobek; in this chapter we read:

“I am a master of glory…to whom the mourners give their hair…”

…I am the one who ejaculates over the mourners…”

If we read the whole speech, we can see that the fact of giving the hair to the dead is a regenerating gesture. Now the word for mourner is smwt. Until now we have read terms like iakbwt or hayt; which come from verbs that mean « to regret ». However smwt seems closer to sema or samt, terms which mean “sorry” or “lament”, but also “lock of hair”.

What is maybe most important here is the new aspect we found in the funerary context: the sex. According to the text, the deceased fertilizes the mourners, in the same way Osiris did it with Isis in the Myth of Osiris. In fact it is again an act for giving life, but now the dead is the one who has this faculty. We will see all over the work, that the erotic element is inseparable from the mourners and the lamentation.

In chapter 167 we read how the dead says:

“…mourner! Get your hair ready for me…”

Here the mourners do not give (rdi) their hairs, but they have it ready (iri) for him. The expression iri sema could refer to brush, clear out, arrange…but it does not seem to refer to show this hair in the same way we have seen before. It is very important to notice here that this chapter treats about the offers to the dead in two festivities: senwt and denit, when the Ancient Egyptians celebrated when the Eye of Horus was completed after the battle against Seth. So we find now a new important element related to the hair: the moon.

The text of chapter 674 is less clear, but also gives a very useful information; in it we read how the mouth of the dead

“…is like the knife ds (the knife ds was used in sacrifices and here it is assimilated to the first quarter of the moon) in Beni Hassan in front of the living ones. Xspr(?), Qbt (Coldness?), my water is the hair of Mht over you…”

This chapter treats also those lunar festivities (senwt and denit) and the dead’s mouth is compared with the ds knife, which is assimilated to the first quarter of the moon and it is considered a defense against the enemies. Also now we find the hair sema likened to the water, another vital element per excellence; and it is important to notice that the word mw can also be translated in Egyptian as “breast milk”, so we would always be in the same revitalizing context.

In Ancient Egypt water was the original element, where the creation came from. And in the funerary processions liquid was poured over the way where the coffin had to pass by.

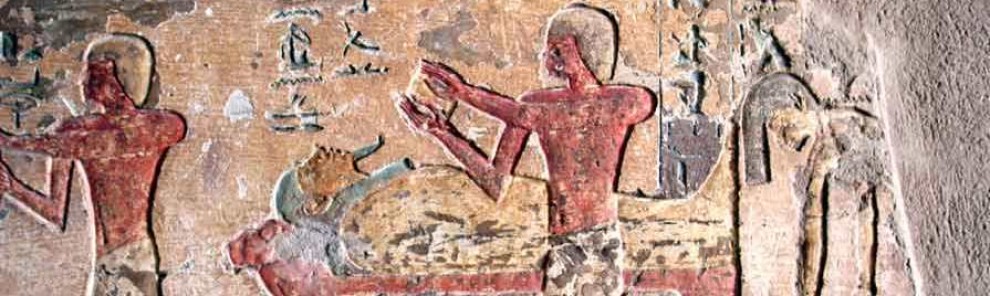

Relief from the Tomb of Maya in Saqqara (XVIII Dynasty). The statue of Maya is being transported on a sledge. Altes Museum (Berlín). Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

According to the inscriptions next to the scenes, this liquid could be water or milk. This action had two reasons, one practical and another one symbolic. On the one hand the liquid avoided the sledge to get hot because of the friction with the ground; on the other hand that could symbolize the moment of the creation, when the order comes from chaos. The image of the coffin over the liquid remembers the first moment of the Primeval Mound coming out from the Primeval Water. In this case we should maybe pay attention to the verb nwn (cover the face with the hair) and notice its script placed between both hieroglyphs of water![]()

We should also point out the tight relationship existing in the symbolic context between the water and the hair. “From the right moment that it is wavy, the hair remembers the aquatic image and vice versa” (Durand, 1979, p. 93). On the other hand, in Ancient Egypt was very common to assimilate the hair with the blue colour (the hair of the divinities was made of lapis lazuli), which is the preferred one for the water. And this also acceptable the opposite way, because the hieroglyph for water was usually coloured in black, as it was also for hair.

Water in blue with the black waves. Tomb of Pashedu in Deir el-Medina. XIX Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

But the hair that is related to the water is the one of women, because the liquid element is feminine (menstruation is liquid); and water and menstruation are regulated by the lunar cycle. Water is also considered in many cultures as a way of purification and renovating, because it can destroy and eliminate the past for coming back to a primitive estate.

In Ancient Egypt the primeval water was called Nwn, from it came out the demiurge that created the world. In this context we cannot avoid thinking of the Egyptian flood. With it starts the Egyptian year and it is the beginning of the agricultural cycle, subsistence of Egyptian people. So, if we assimilate the water Nwn with the hair sema, why not think about a relationship between the hair sema and the nwn gesture as a beginning of a new life?

It is clear that there is an interrelation water-hair sema-moon-maternity-femininity in the funerary process of resurrection, and that femininity would explain why the role of mourning women is so relevant. These Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom are saying us that the hair of the two mourners representing Isis and Nephtys played an important role in the funerary context of Ancient Egypt.