All along this work we have found three different mourners involved in Egyptian funerals.

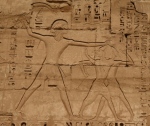

Mourning men pulling hair. Relief from the mastaba of Idu in Gizah. VI Dynasty. Photo: http://www.antiguoegipto.org

On one hand there were groups of common mourners (mainly women, but sometimes also men) among the rest of the members of the cortège. They were walking together weeping and making the typical gestures of mourning: beating themselves, raising arms, ripping their clothes…those gesture included also to shake the hair and cover the face with it (nwn) or to pull a front lock of hair (nwn m). Egyptian documents (texts and iconography) do not give evidence that both gestures were made together; common mourners made one or another nor did the whole group do the same gesture all together. It seems that there was no coordination and that the women could make different mourning movements during the procession. The question is if that depended on something.

- Was it something spontaneous and did it not depend on any order?

- Was it an election of priests?

- Did it depend on a local custom?

- Was it an election made by the deceased’s family?

- Was it an election made by the deceased? Taking into account that the tomb and its decoration was made while he was alive, it makes sense to think about a tomb’s owner election.

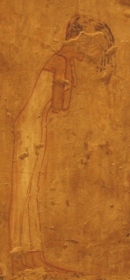

On the other hand, Egyptian iconography, specially tombs and papyrus from New Kingdom, show us the deceased’s widow next to the coffin also weeping and making mourning gestures, but apparently never shaking or pulling her hair. She is a mourning wife, but different from the group of common mourners and from the two representatives of Isis and Nephtys.

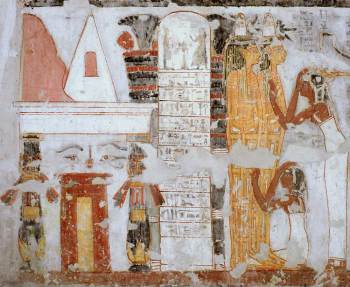

Isis and Nephtys are at both extremes of the mummy. Behind Roy’s wife mourns her husband’s death. Painting from the tomb of Roy in Dra Abu el-Naga. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

Finally, the funerary ceremony in Ancient Egypt counted on the participation of two mourning women playing the roles of Isis and Nepthys. The New Kingdom is the most prolific period of Egyptian history in scenes of them. They usually appear at both extremes of the coffin with a passive attitude, although funerary texts refer to them as active members in the corpse’s regeneration.

If we construct the puzzle with all the pieces from the different documents the scene we have is the following: during the cortège these two professional mourners stood static next to the mummy and with their hair covered by a piece of clothing, meanwhile the rest of mourners regretted the death of a person crying, screaming and shaking and/or pulling hair. Once the procession arrived to the necropolis things changed.

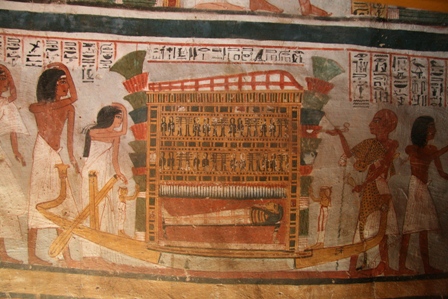

Cortège with the common mourners, the deceased’s wife and the two Drty in the role of Isis and Nephtys. Papyrus of Nebqed. Musée du Louvre. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.eu.art.com

Mourners over the corpse. Detail of the stele of Akbaou. Musée du Louvre. XI Dynasty. Photo: http://www.commons-wikimedia.org

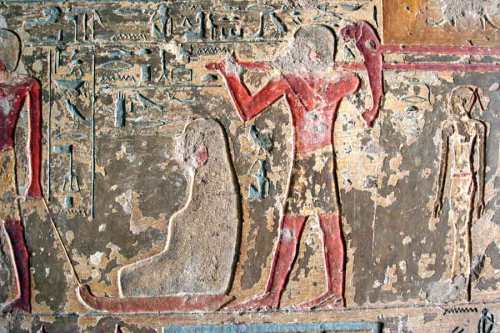

The Opening of the Mouth ceremony for reviving the mummy took part somewhere in an enclosed area (most probably the tomb) and not in view of anyone. It was when the priestly team entered into the mythical dimension; the myth became rite in a group of practices for getting the deceased’s resurrection. The two women (Drty) turned into Isis and Nephtys and the mummy into Osiris. Outside the common mourners (included the deceased’s wife) kept moaning, but inside the two “kites” carried out a mourning ritual in which they made the nwn and the nwn m gestures. This way they reproduced that part of the Osiris myth in which Isis conceived Horus and he could revenge his father’s death.

During the Opening of the Mouth ceremony the sem priest played the role of the tekenu, helping in the transmission of life force to the corpse, but he also was the representative of Horus for facing Seth. This part of the myth is materialised in the rite by means of the sacrifice of an ox.

Sacrifice of the ox with the presence of the mourner. Painting from the tomb of Rekhmire in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

The animal’s slaughter meant the victory of Horus over Seth, the good over the evil, so the mourning’s end. At that moment we consider the s3mt was cut, cutting this mourner’s hair symbolized the enemies’ annihilation, the end of the mourning and the Udjat eye’s recovery.

The two Drty (two kites), offering nw vases to the four pools, both with short hair. Relief from the tomb of Pahery in el-Kab. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

At the end of the Opening of the Mouth ceremony there were, among others, a hair offering. It was the mourner’s hair that had been shook and pulled and that served for symbolizing the revitalization process of the mummy (recovery of vital faculties, return to the Nun and to the womb…) and the removal of the evil which could drag out that process (lunar eye suffering, enemies, chaos…). This hair was offered as an image of the Udjat eye and materialised the deceased’s resurrection.