We have already seen the importance of Hathor and her two ringlets in the Ancient Egypt funerary imagery and symbolism. This goddess has many epithets which link her directly with the hair element; she is the “Lady of the plait” (Hnskt) or « the One of plait » (Hnsktt, Hnkstt)[1]. Also the priestesses who took part in the Hathor mysteries were called « the ones with plaits » (Hnskywt) or « the ones with ringlets » (wprtywt)[2].

There is a fragment of the Ramesseum Papyrus XI, where we read: “Mi heart is for you, my heart is for you as the heart of Horus is for his eye, the one of Set for his testicles, the one of Hathor for her plait, the one of Thoth for his shoulder[3]”. The text is mentioning mutilations suffered by these gods, so maybe were there an Egyptian myth where Hathor could lose a plait of hair? If so, we could then understand why in some magical practises dedicated to Hathor there had to use a plait of hair[4].

We must also take into consideration that in the Egyptian religion Hathor and Isis were associated. Plutarco assured that Isis pulled herself a lock of hair out when she knew about Osiris’ death[5]; this assertion makes us think of the image of mourners pulling their hair in funerals. We could link that with the damages mentioned above suffered by those gods in some parts of their bodies found in the text of Ramesseum Papyrus; however we have also to consider:

1) The iconography just shows us the gesture of pulling the lock of hair, but not the mutilation Plutarco mentions.

2) Ramesseum Papyrus mentions mutilations caused by another one to the god. In the case of Isis we would not be facing an attack to the goddess, but a self lesion.

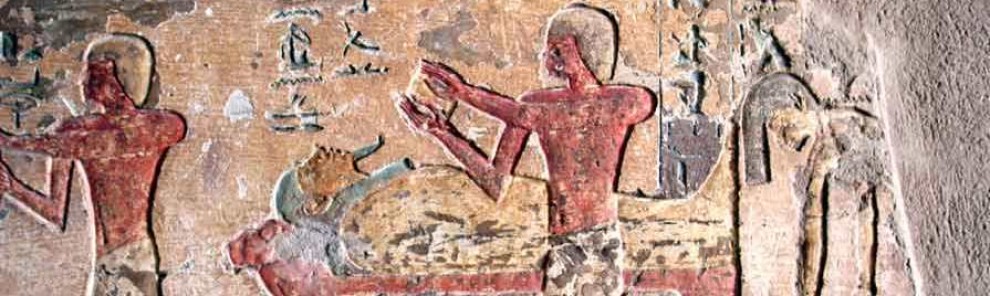

Hathor and the loss of hair derives us to some statues dating from New Kingdom representing men sit in front of an Hathor’s symbol and which were studied by J.J. Clère[6]. Those men either they are bald, or they were supposed to be bald[7], because the inscription in all of them describe them as « the bald of Hathor ».![]()

The Egyptian word for « bald » is is o ias![]() , which defines the natural baldness, that is, the alopecia[8]. J.J. Clère considers that the term ias would have two senses: on one hand it would be « bald » in the most generic meaning, and on the other hand it would allude to the “sincipital baldness”[9]. That is, the alopecia in the upper half of the cranium, so the baldness in the wpt, as in the statues of the ias priests of Hathor[10], who had to be bald.

, which defines the natural baldness, that is, the alopecia[8]. J.J. Clère considers that the term ias would have two senses: on one hand it would be « bald » in the most generic meaning, and on the other hand it would allude to the “sincipital baldness”[9]. That is, the alopecia in the upper half of the cranium, so the baldness in the wpt, as in the statues of the ias priests of Hathor[10], who had to be bald.

Head fragment from a statue of a “Bald of Hathor”. New Kingdom. Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York. Photo: http://www.metmuseum.org

Around this matter it is interesting to have a look on a sentence in the Songs of Isis and Nephtys, which although very incomplete, could gain sense with all we have seen until now:

“…the baldness on the top of the head…” [11].

J.J. Clère did not see the relationship between this partial sentence and the context it is written[12], but in fact it has, because that text is mentioning the damage that Seth has caused: « Seth is in every bad thing he has done » [13], «he has messed up the sky administration» [14], «and he has sent to us bad intentions» [15]. Could we think about a version of the Myth of Osiris, where Seth amputated the hnskt of Hathor? That would explain the comparison with the eye of Horus and the testicle of Re.

That being the case, the term is/ias would describe a sincipital baldness, however not a natural alopecia, but one caused by mutilation; ias would refer to an involuntary loss of the hair, while the term f3k would refer to the voluntary shave.

Equally we could think that Hnskt would be not just a lock of hair falling on the back, but also the hair in the top of the head (wpt). The priesthood of Hathor in the statuary lacks the hair on the wpt; the top of the head; where Hathor, as the cow goddess, has her horns. Could we then think of assimilation between the hair and the horns? If so, then we should also think about a possible version of the Myth of Osiris where Seth damaged Hathor’s horns. Maybe it would be more reasonable to consider that the Hathor in the Ramesseum Papyrus was in fact Isis, the mourning wife pulling her lock of hair as a despair gesture when she knew about the death of Osiris at the hands of Seth. In addition, the title of those ias priests in some statues refers to Isis: “I am the bald of Isis, the Big One” [16] ; « I am a bald one, excellent, favourite of Isis » [17].

Maybe for being assimilated to Isis, Hathor was a divinity very closed to Osiris in the Egyptian religion and it was very common to find her in images accompanying Osiris[18]. But her presence was not just in iconography; in celebrations in honour to Osiris during the month of Khoiak Hathor had also an important role. For instance, in the Middle Kingdom there was at the beginning of the month a sailing of Hathor. This goddess also appears six times accompanying Isis in the Festival of Sokaris (god assimilated to Osiris); her boat guides the other ones and the rest of goddesses are considered as different forms of Hathor[19].

Anyway, statues of ias priest show them always with an hathoric symbol; those men belonged to an Hathor’s clergy, who had to lack hair in the top of the head, apparently not voluntary; maybe in honour to the goddess, who suffered a mutilation with a similar result in her body.

“Bald of Hathor” Ameneminet. XIX Dynasty. Luxor Museum. Photo: http://www.eternalegypt.org

Summing up, we have three main points related to Hathor and the hair:

- Hathor related to the two ringlets wprty. These two lateral ringlets are like the two sky doors, which open and allow the deceased to go up to the celestial sphere and see the face of the lunar goddess, that is the moon, so the light in the darkness. The wprty are a grant of resurrection.

- Hathor or Isis had a possible loss of hair (hnskt), as it was a mutilation, similar to that one suffered by Horus with his eye or Seth with his testicle.

- Existence of a clergy of Hathor, whose requirement was the lack of hair on the top of the head (wpt), showing this way a relationship between Hathor and the lack or loss of hair.

[1] G. Posener, 1986, p. 113.

[2]S.A. Naguib, 1990, p. 13.

[3] According to some versions Seth attacked Thoth and cut off his arm. G. Posener, 1986, p. 111.

[4] Pap. Berlin 3027 9, 3-7; A. Ermann, 1901, p. 34. Although here the Egyptian word for plait is not Hnskt, but dbnt. Some scholars assure that there are representations of locks of hair with hathoric symbols of regeneration. E. Staehelin, 1978, p. 83.

[5] Plutarco, De Iside et Osiride, 14.

[6] J-J. Clère, 1995.

[7] J-J. Clère, 1995, p. 14.

[8] There is another Egyptian term for “bald”: f3k, used for the priesthood of Heliopolis. Actually it refers to the “shave”, not to the natural baldness. We have already written about the baldness and the lack of vegetation.

[9] J-J. Clère, 1995, p. 28.

[10] We read in the chapter 588 of the Coffin Texts and chapter 103 of the Book of Dead: “Speech for being at both sides of Hathor. I am one who has passed pure, a iAs priest. I will be Ihy in the Hathor’s entourage”.

[11] Pap. Bremner-Rhind, 2, 23.

[12] J-J. Clère, 1995, p. 30.

[13] Songs…, 2, 19.

[14] Songs…, 2, 20.

[15] Songs…, 2, 21.

[16] J-J. Clère, 1995, p. 76.

[17] J-J. Clère, 1995, p. 160.

[18] This assimilation comes from the Old Kingdom. Also in some cases Isis can appear as Re’s wife.

[19] Papyrus Bremner-Rhind ,19, 13 ff.