In Egyptian religion, Osiris is the god of death, but also of vegetation and his myth has an erotic component. According to M. Eliade “moments of cosmic crisis are a pretext for the unleashing of an orgy. The earth needs to be revived and the sky needs to be excited, to make the good conditions for the cosmic Hierogamy; this way cereal grows up, women engender children, animals reproduce and dead ones full their vacuum with vital power”[1].

From the basis of the Eliade’s theory, orgy is an act of renovation and regeneration; it is a way of coming back to the first moment just before the final creation, when still chaos and confusion dominate the existence. After the orgy a new life starts and with it the chaos disappears and the world is reorganised; the orgy is the experience of the original state[2].

Orgy is even the image of chaos. Orgiastic festivities allude to the chaotic moment in which the world is lost and from where the new power comes out for reorganising and restoring the cosmic order. As J. E. Cirlot says “the goal is not to obtain physical pleasure, but to help the world dissoluteness; a temporary breaking-off for the following restoration of the original “illud tempus”[3]. Orgy is, then, according to scholars, an act which generates life.

The connexion of orgy with life could make us think of the relationship also with the moon, because it is a star which remakes and renews itself. The moon is also the night star, when chaos and darkness reign. And it is in the same way related to vegetation, since agricultural rites are also lunar rites due to their regeneration nature. In fact, from prehistoric times, lunar symbols have erotic connotations thanks to the analogy between vulva and shell; for instance, the spiral is a sign that derivates from the snail shell; and this animal, which appears and disappears, is usually assimilated to the moon, and also for that same analogy the spiral has an erotic nuance[4].

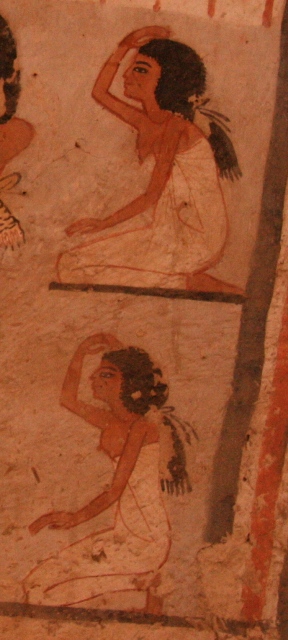

We can guess that in Ancient Egypt funerary ceremony, mourners representing Isis and Nepthtys and the gesture nwn of shaking hair smA onwards could also have an erotic nature, whose goal was to help the dead come back to life. For some scholars “the spreading through sexual act could be considered according to primitive thought, as an alternative to the eternal life”[5]. The fertilizing nature of copulation seems to be united to resurrection as a regenerating element. It is the union of the two principles, masculine and feminine, the union that in the Creation myth produces the first manifestation of life.

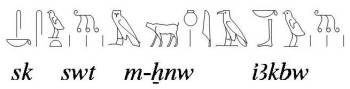

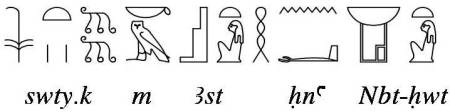

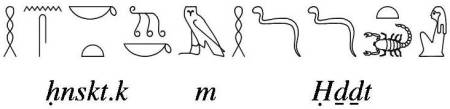

In this regard, we cannot forget to mention chapter 17 of Book of the Dead, which captures perfectly all we have been talking about[6]:

“I am Isis, you found me when[7] I had my hair disordered[8] over my face, and my crown[9] was dishevelled[10]. I have conceived[11] as Isis, I have procreated as Nephtys.

Isis dispels my bothers (?)[12]. My crown is dishevelled; Isis has been over her secret, she has stood up[13] and has cleaned[14] her hair”[15]

H. Goedicke states that the chapter is describing clearly the copulation of Isis and Osiris[16]. Isis, making the nwn gesture put herself over the body of her husband Osiris, who lies face up; she gets pregnant and protects the dead. All that practice is her secret; afterwards she stands up and does her hair. It is also interesting to point out that in Papyrus Turin, just before that we read: “…both sisters are given to me for pleasure…”[17]

It seems clear the relationship between the dishevelled hair and the sexual act; especially if we consider that the verb “dishevel” (txtx) has the same root as « inebriation » (txi).

According to A. Gutbub, the festivity of inebriation in honour of Hathor which was a part of the Festival of the Valley maybe was also celebrated in funerals in honour of the deceased[18]. The scholar considers also that the ritual wpi hn made in the Sed Festival could be interpreted as the union of Hathor with the king during an inebriation celebration[19]. That being the case, the sexual element would be a part of funerary-initiation rites; in them the goal is the change of status of the initiated one by means of returning to the primeval moment and the subsequent rebirth.

The Osiris legend tells that Isis invented during the mummification the remedy for getting the immortality, but it was not enough. She had to assure a descendent of the deceased, because the earth needed an heir for the throne, who also had to help in his father’s resurrection. Isis became a kite, flapped her wings and revived her husband; with this gesture she could also conceive her son Horus, but this “is something that needs to be hidden, it is not allowed that a man or a woman divulges it aloud” [20]. Maybe that is the reason of describing the act as « secret » and could also explain the shortage of documents.

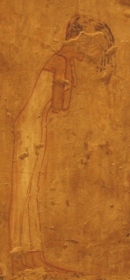

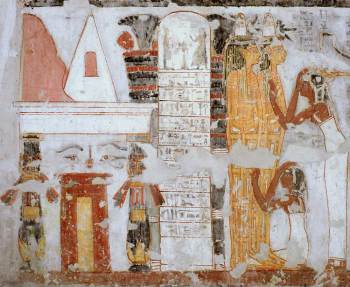

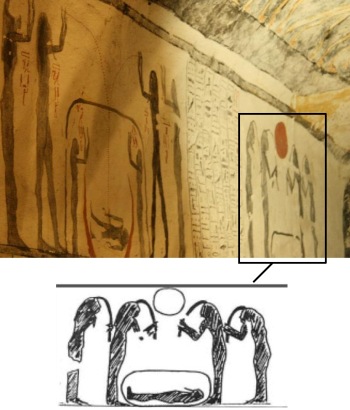

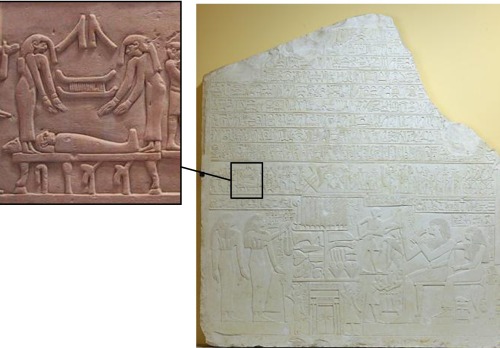

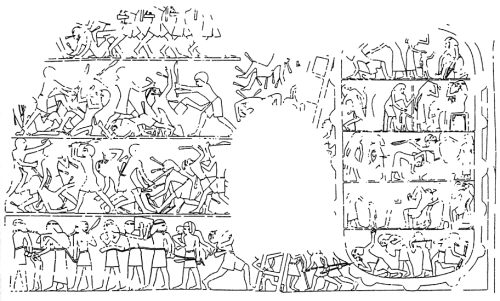

It is important for that matter to mention one scene of resurrection in the tomb of Petosiris. The deceased, assimilated with Osiris and represented as a scarab with the atef crown, has the goddess Isis on both sides.

Scene from the tomb of Petosiris in Tuna el-Gebel. The deceased in the middle, as ascarab with atef crown, is flanked by Nekhbet and Uadyet and by two late versions of Isis. Late Period.

The Isis in the right hand is represented with the sign of the full sail, symbol of breath and wind; in this scene the goddess is called the Lady of the North, the Lady of vivifying wind, while Osiris is on copulation:

“Words said by Isis, Lady of the red crown: the north wind is destined to your nose…I made your throat breath. The divine mother, she joined the limbs of her brother in the palace. They look for Osiris…he is in copulation” [21].

In this passage we read about the breath of life and the sexual act, both apparently evoked by the nwn gesture. This posture would recall the Osiris legend, when Isis as a kite lands over her husband, she flaps her wings for giving him the breath of life and put herself over his phallus for giving him back his virility and conceive Horus. The birth of the son means the victory over the temporality by means of perpetuity of the lineage; the second element is result and image of the former one[22]. The son is the image of eternity and balance in the same person, as result of the creation.

It makes sense then to think about the nwn gesture in funerals made for the mourners representing Isis and Nephtys (by extension) as a way of remembering the sexual episode of the Osiris myth, but in the most human version.

[1] Eliade, 1970, p. 301.

[2] Durand, 1979, p. 297.

[3] Cirlot, 1991, p. 341.

[4] Elíade, 1970, p. 140.

[5] Briffault, 1974, p. 313.

[6] Urk.V, 87, 1-7; Urk. V, 89, 1-3.

[7] sDm.n.f expressing past tense.

[8] The verb psx can be transitive: “dishevel the hair” or intransitive: “be crazy”, “despair”. It could also refer to the disorder of the hair or of the heart because of fear (Wb I, 550, 16).

[9] Wpt can be translated as “crown” or the top of the head. RA can be “the beginning”, as the origin of the scalp, where the hair starts, so the “crown”; or also the beginning of the hair from the face, so, the forehead.

[10] txtx is to dishevel the hair (Wb V, 328, 8).

[11] The verb iwr means “conceive”, “be pregnant” (Wb I, 56, 1).

[12] According to Erman and Grapow, sAwt means “safe-keeping” (Wb III, 418, 5); but if we apply this translation, the sentence makes no sense. In another version of chapter 17 of Book of the Dead, with Dr.s sAwt.i, we read: Nb-Hwt bHn.s Xnnw.i (Junker, 1917, p. 157). BHn means “cut” or “eliminate” (Wb I, 468, 10; Faulkner, 1988, p. 83), as a parallel with Dr; and Xnnw means “disturbance”, “disorder” (Wb III, 383, 15; Faulkner, 1988, p. 203), so sAwt maybe has a similar meaning.

[13] aha.n sDm.n.f can be a narrative tense, so it could be translated as “then”. But if we consider aha as a verb, the translation should be “she stood up”.

[14] sin means “clean”, “scrub” (Wb III, 425, 8; Faulkner, 1988, p. 213). It would be possible to think of Isis standing up and doing her hair after dishevel. (txtx).

[15] Urk. V, 87, 1-4 y Urk. 88, 17- 89,3.

[16] Goedicke, 1970, p. 25. He also thinks that there is a passage in Pap. Chester Beatty I, 16, 10-11 and in Pap. Westcar 2, 1.

[17] Rachewiltz, 1989, p. 59.

[18] Gutbub, 1961, p. 50.

[19] Gutbub, 1961, p. 60.

[20] Books of Breathing cf. Desroches-Noblecourt, 1968.

[21] Daumas, 1960, p. 68, pl. I.

[22] Durand, 1979, p. 290.