S3mt was for Egyptians apparently something more than just “mourning”. What about that s3mt that could be cut, which was related to snake uraeus, which appears in a moment of restoring some parts of the mummy and which was also an offer to the deceased? In chapters 532 and 640 of Coffin Texts the s3mt is cut and also tied around the dead one, when his neck and head are also restored. Do we have any other documents where to find more clues?

Chapter 50 of Book of the Dead was the heir of the chapter 640 of the Coffin Texts and belongs to a group of chapters related to the regeneration of the corpse. In a Ptolemaic version in the Egyptian Museum in Turin we can read: “Formula for not entering the butchering hall of the god. Speech said by Osiris, alive and justified: my vertebrae are united in my nape by them, the Ennead. My vertebrae are united in my nape (bis) in the sky and on earth by Re, in that day of reinforce and reconstitute the exhausted ones[1] over the two legs, in that day of cutting the necks[2]. The vertebrae in the nape are united by Seth with his power, when[3] there was no disturbance”.

But in some other versions of the same chapter we read a very similar text to that one of the Middle Kingdom: “…fours knots have been tied around me by the sky’s guardian, he has fixed a knot to the dead ones over the legs in that day of cutting the lock of hair s3mt….”

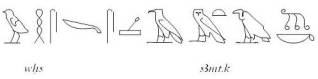

At this point it is important to notice that the writing for the Egyptian word nHbwt (necks) had the determinative of hair:![]() . It seems that cutting the lock of hair s3mt is interchangeable with cutting the necks. So there was in ancient Egyptian belief assimilation between both hair and necks, which would mean that cutting the necks, would be the same act as cutting the s3mt.

. It seems that cutting the lock of hair s3mt is interchangeable with cutting the necks. So there was in ancient Egyptian belief assimilation between both hair and necks, which would mean that cutting the necks, would be the same act as cutting the s3mt.

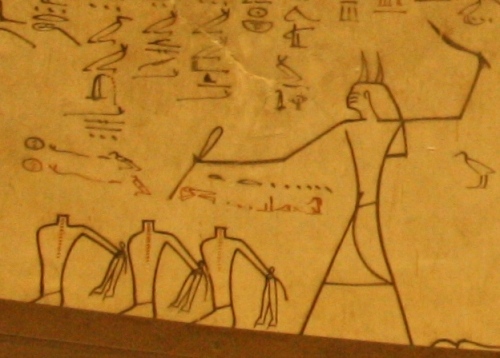

Hair and necks, what can that have to do with the snakes? In this regards it is interesting J.F. Borghouts comment about chapter 532 of the Coffin Texts where we have already read about a Heliopolitan rite: “…Is tied to me a lock of hair in Heliopolis, the day of cutting the lock s3mt” [4]. J. F. Borghouts focus on the beginning of the passage: “Formula for placing a man’s head in the necropolis…” The passage relates how the deceased receives his head and his neck at the same time that the gods receive their heads, and that action happens the same day that the s3bwt snakes (or multi colour snakes) were expelled from Heliopolis, because they caused the gods to lose their heads[5]. The s3bwt snakes where the enemies of the Sun god because they injured the gods and let them headless. We would be facing an archetype “rite of defeating the evil one”, where the Demiurge announces: “I have appeased the Heliopolis’ disturbance after the judgement, I have restored the heads to those ones who had them not, and I have finished the mourning in this country” [6].

Beheading the snake as an image of the evil. The cat of Heliopolis killing the snake Apohis, enemy of Re. Painting from the tomb of Inerkha in Deir el-Medina. XIX Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

The head is the central of the body for all senses, not having head means not having faculties of perception and it is also a lack of identity. In Egyptian funerary belief, the lack of head is, not only the obvious lack of life, it is also the impossibility of resurrection. To restore the head is a step to the new life, since thanks to it the deceased will have again the faculty of breathing, seeing, listening[7]. In line with that is the Egyptian union between headless Osiris and the invisibility of the new moon[8]; the disappearance of the head is like the disappearance of the moon, it is the darkness, and so, it is the death. When a human being dyes he gets into a period of shadows, which fades gradually at the same time of the funerary rites. Among these rites here we need to mention the put of the funerary mask, which was a head’s substitute; with it the dead one will have again access to light, to the new life.

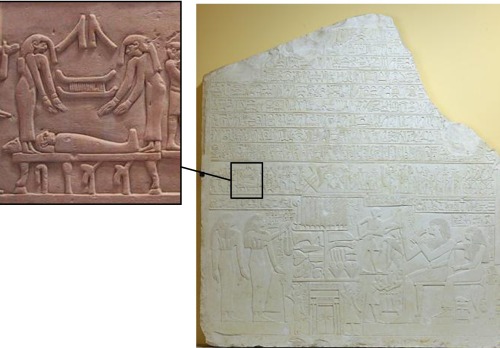

There is a stela found in Abydos and dating from the reign of Ramses VI where we can read: Oh! Horus, I have spitted over your eye, after it was removed by your aggressor…Oh! Isis and Nephtys, I make bring[9] to you your heads, I have put[10] your napes for you in this night of cutting[11] the heads (?) of s3bwt snakes in front of Letopolis…”[12] The text reminds to the former chapters we have already seen about the healing of the damaged lunar eye and the shaving of the two mourners.

The healing of the Udjat eye happens at the same time of the gods’ heads restoring and the revenge over the s3bwt snakes. And cutting the s3mt could be the same as cutting the s3bwt.

According to J. F. Borghouts, the parallel between s3mt and s3bwt could be caused by a deformation in the writing with the passage of the time. But so many times repeating the expression “cutting the s3mt” would maybe respond more to assimilation with “cutting the s3bwt” than just a mistake in the writing. The result would be in line with our research: the lock of hair s3mt would be identified the the s3bwt snakes as a negative element that needs to be eliminated. So, to cut the s3mt would symbolize a sacrifice of a dangerous animal. The hymn to Sobek in Ramesseum Papyrus says:

“Welcome in peace, lord of peace!

Your fury has been eliminated; your anger has passed…

Your s3mt is cut” [13].

The Egyptian verb whs was used for “cutting hair”, but also for “sacrificing enemies” [14], and that put in the same level to cut the lock of hair s3mt and to sacrifice an adversary. Hair, enemy and sacrifice are already familiar concepts to us.

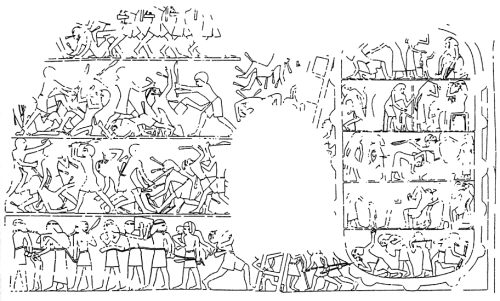

Beheading the enemies of Osiris. Painting from the tomb of Tutmosis III in the Valley of the Kings. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

Let’s compile some ideas to give shape to our post:

- The day of shaving the mourners is the day of giving the Udjat eye.

- To equip with a lock of hair s3mt appears at the same time of shaving the i3rty of Sokaris.

- The s3mt is cut when the deceased is still blind/dead and after that action he has access to light/new life.

- To spit over the damaged eye of Horus for healing it, to restore the gods’ heads and napes and to cut the heads of the s3bwt snakes, the enemies, happened together.

Summing up, we find four elements together in the deceased’s regeneration:

- Slaughter the s3bwt snakes as the evil ones.

- Cut the s3mt

- Restore the heads

- Recover the Udjat eye.

The two first ones are similar actions for eliminating the evil and after them the two last ones are actions which meant the perception and the access to light, so the deceased’s resurrection.

[1] The dead ones.

[3] From XVIII Dynasty on, preposition tp could have a temporal sense.

[4] We have seen this chapter in the first paragraph about the lock of hair s3mt.

[5] J. F. Borghouts, 1970, p. 73.

[6] Urk. VI, 115, 9-15 (D. Meeks, 1991, p. 6. The Egyptians thought that Horus from Letopolis was the one who restored the gods’ heads. The day commemorating that was a festivity in Heliopolis (J.F. Borghouts, 1970, p. 206)

[7] D. Meeks, 1991, p. 6.

[8] D. Meeks, 1991, p. 8

[9] siar means “make go up”, in the sense of “bring” or “give” (Wb IV, 32, 10)

[10] smn means “join”, “bind”, “put” limbs that have been separated (Wb IV, 132, 20)

[11] The generic meaning of sn es “decapitate” (Wb III, 457, 17).

[12] KRI VI, p.24, 3-4; M.Korostovtsev, 1947, pp. 155-173.

[13] A. Gardiner, 1957, p. 46.

[14] Wb I, 351, 14.