During these days we have seen how iconography and texts proof the existence of a gesture, posture or movement made by mourners in Ancient Egypt funerals. Sometimes they pulled their front lock of hair (nwn m) and sometimes they shook their mane onwards covering their faces with it (nwn). In both cases there was always an implicit symbolism, mostly related to the Osiris legend and the resurrection of the dead.

But now many questions come to mind: when did these women do that gesture during the funerary ceremony? Was the mourning rite constant during the whole ceremony or was just for some special moments? Were the normal mourners and the representatives of Isis and Nephtys making it together and/or at the same time?

Firstly we should distinguish the common mourners from the two women in the role of Isis and Nephtys. It makes sense to think about two different kind of performance. The iconography has several examples of mourners “outdoors” making the nwn m or nwn gesture. They would be part of the group of women accompanying the coffin in the funerary procession, we see them in movement in the reliefs from the tombs of Mereruka and Idu or in the Middle Kingdom coffin from Abydos; but also we see them in a more static moment, when some mourners are sit while others are making the nwn gesture, as in the tombs of Amenemhat, Miankht or Rekhmire.

From the iconography we could deduce that the nwn gesture made by common mourners could take place:

-During the procession, while the coffin was transported.

-In necropolis, when the retinue has already close to the burial.

-Both, first during the procession and second once the retinue were in the necropolis, while the body was being buried.

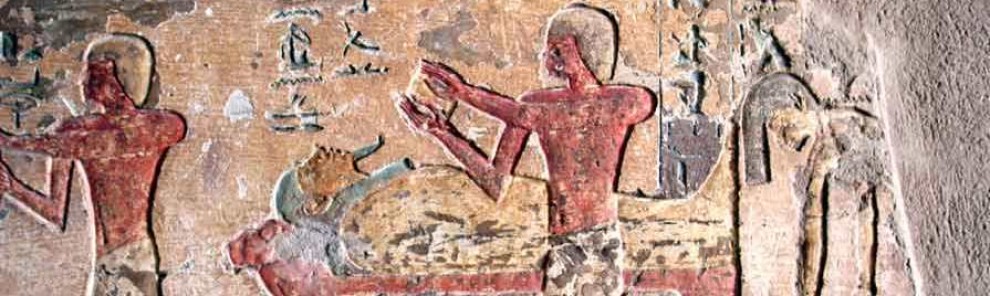

Mourners. Painting from the tomb of Rekhmire in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín

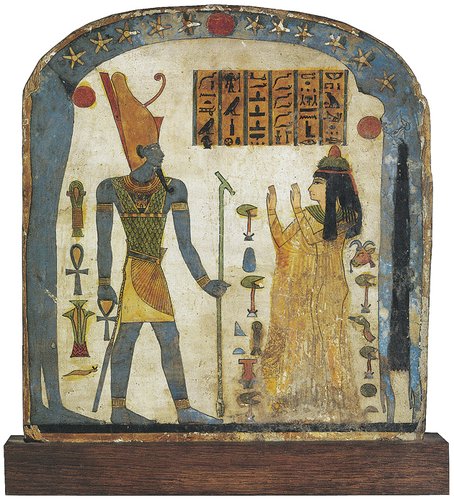

However we only have Isis and Nephtys in iconography making the nwn gesture in the stele C15 from the Middle Kingdom (the whole scene represents the Osiris Festivity) and the funerary temple of Seti I in Dra Abu el-Naga and also pulling their front lock of hair (nwn m) in the coffin of Ramses IV and the one of dwarf Djedhor. Religious texts mention how the goddesses make the nwn gesture and show or give the hair sema to the deceased. It does not seem to be a public moment, but a more secret practice and closely linked to the corpse and the resurrection of the dead. If so, the two mourners representing Isis and Nephtys would be two selected women for representing a divine role. And maybe their mourn ritual with their hair was a part of the group of practices made for the resurrection of the dead.

Mourners over the corpse. Detail of the stele of Akbaou (stele C15). XI Dynasty. Photo: http://www.commons-wikimedia.org

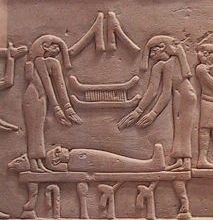

In Ancient Egyptian funerals there was a ceremony for restoring the deceased’s faculties: the ceremony of the Opening of the Mouth, which ended with the final resurrection of the dead. Was it maybe during that ritual when the two mourners made their mourning gesture with their hair? As we will see further in this work, the Ceremony of the Opening of the Mouth was not a public ceremony, but a rite reserved for those who accomplished it, as they were the sem priest, the lector priest and the two mourners. It consisted of a group of practices in favour of the deceased; the goal was to restore all the faculties he needed for his resurrection and his new life in the Herefater: breathing, eyesight, mobility, sexuality… Those practises were made over the mummy or the statue of the deceased and it seems reasonable to think that the mourners in the role of Isis and Nephtys did their nwn gesture near the body in some moment during the Ceremony of the Opening of the Mouth. In fact it is usual to find in the Egyptian iconography many scenes of that ceremony with the presence of mourners; maybe the most explicit one would be the one in the tomb of Renni, where we can see how priest is making the ritual over the corpse and the statue, while a mourner is making the nwn gesture.

Opening of the Mouth with mourner in nwn gesture on the right. Tomb of Renni in el-Kab. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.oisplendorsofthenile.blogspot.com.es

Summing up, the nwn and nwn m gesture had two dimensions, with different meanings and in different moments of the funerary ceremony. The public one made by common mourners outdoors during the procession or out of the tomb in the necropolis; and the private one, made by the two women in the divine role of Isis and Nephtys for the resurrection of the dead. In the first case the nwn/nwn m gesture is related to the chaos, the darkness of the death and is a sign of despair. In the second one those same practices had a revivifying goal.