Udjat eye in a Middle Kingdom coffin. Beni Suef Museum. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

Once the damaged eye of Horus, that was related with the hair sm3, has been healed it becomes the Udjat eye, the full moon as a symbol of the total regeneration. The question is does this aspect of the lunar eye have any connection with the hair? The answer is yes, it does.

Some chapters of the Coffin Texts relates the final episode of the Egyptian myth of Osiris, when he gets triumphant over his enemies and he is reborn; on earth that means the deceased’s resurrection. It is when Horus gets his eye back, his Udjat eye, and it is interesting to notice how in that moment the funerary texts mention two very relevant things:

- The presence of the lock of hair (or just hair) s3mt.

- The shave of the mourners.

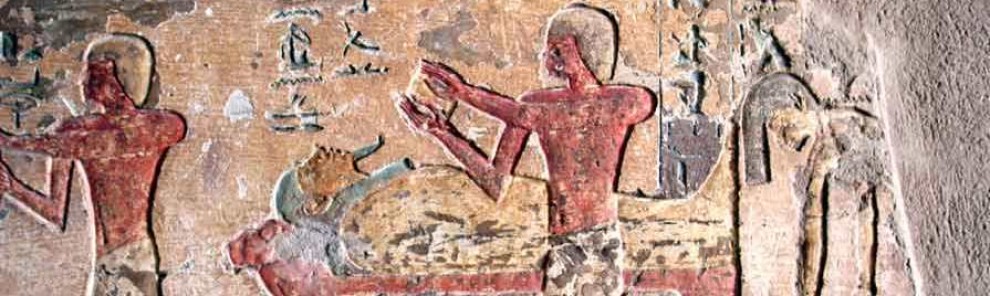

Chapter 339 is about the Osiris’ victory over the enemies and his resurrection. It mentions towns related somehow with Osiris and his burial: Busiris (where was the Osiris’ spine), Letopolis (here was the shoulder), Buto (the ladies of Buto crying for Osiris were Isis and Nephtys), Abydos (where was his head and his burial place)…; Thoth appears as the god claiming “true of voice” Osiris, Horus also offers his Udjat eye to his father[1]; with that act culminates the final resurrection, it means the end of the chaos, the order restitution and the beginning of the new life. Osiris is reborn as king of the Herafter, while Horus inherits the throne of Egypt. And, according to chapter 339, that moment of restoration is the moment of shaving the mourners in Buto, so shaving Isis and Nephtys:

“…Busiris, this is the day of giving the Udjat eye to his lord. Pe-Dep[2], this is the day of shaving the mourners…”

Razor made of bronze and wood, coming from the tomb of Hatnofer and Ramose in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty. The Metropiltan Museum oj Art of New York. Photo: http://www.metmuseum.org

Chapter 942 is too damaged, but it seems to allude to the fight between Horus and Seth:

“Provide with her s3mt burning (?)…

Those ones from Hermopolis adore him [3](…), they break the double power. My coming up is the coming up of this goddess, raising with Re…the only lord, which has taken the flame of the Luminous One.

The two i3rty of Sokaris[4] are shaved for her

The face is adorned [5](…) made against her in the name of Wnwt[6]. Seth is put by her under her pleats (…) the peace is made (…) in their names. I am alive and intact, they are alive and intact ».

When Seth is put under Wnwt, which is related to the uraeus snake, the peace is made because in Egyptian belief the uraeus is benefactor; it eliminates the evil (Seth), that is, it helps in restoring the universal order.

Uraeus on the forehead of Amenhotep I. XII Dynasty. Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

What about the hair elements we find in the text? P. Barguet translated the first sentence as: “her plait is destroyed”. If the word instead of s3mt were sm3, we could maybe think of an allusion to the damage suffered by the lunar eye, but if we look at verb, Htm could be also translated as “provide with”, “equip with”, and specially “equip the face with the eye” [7].

Regarding the i3rty, the dual form and the hair determinative make us think of the two mourners Isis and Nephtys. I3r means « sadness » or « mourning » [8]. R.O. Faulkner translated the term i3rr  as “weakness of the eye” or “weakness of the heart” [9]. On the other hand, i3rt

as “weakness of the eye” or “weakness of the heart” [9]. On the other hand, i3rt  is also an Egyptian expression that designates the uraeus snake of Re[10] ; so we could also consider that the i3rty would be the two uraei of Sokaris, which will be shaved.

is also an Egyptian expression that designates the uraeus snake of Re[10] ; so we could also consider that the i3rty would be the two uraei of Sokaris, which will be shaved.

The meaning of Haq is “shave”, so it is applied just to hair. The question is why is it here used with snakes instead of hair? It is no new for us the Egyptian assimilation of both elements, since we have already seen how the plait Hnskt was identified with the snake as symbols of rebirth. For that same reason it would not be so crazy to consider that in Ancient Egypt the two uraei could be identified with both locks of hair s3mt.

Statuettes of Isis and Nephtys mourning. Ptolemaic Period. Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York. Photo: http://www.metmuseum.org

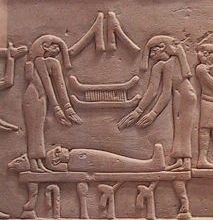

So, the chapter 942 would be relating the shave of the uraei, which would be the same as saying that the two locks of hair were cut. With these i3rty of Sokaris maybe we would be facing again a new case of metonymy, the two mourners being mentioned through their most relevant part: the i3rty, so it would be a way of describing Isis and Nephtys. Maybe we are reading about the shave of both mourners’ locks of hair, and these ones assimilated to two uraei as victors over the evil.

After shaving the i3rty (locks of hair or uraei) the text says how the face is adorned or dressed, but…with what? Do we have to think about the arrangement of the Udjat eye on the Osiris/deceased’s face? If so, why is it related to the locks of hair and its shaving?

Finally, we have another passage in Coffin Texts showing a very narrow relationship between lock of hair and eye. In chapter 1131 the deceased is at the same level of Osiris, that one is described as an image of the god. In this context the dead one goes ahead to his resurrection and one of the things happening before that is the following:

“… The lock of hair (or just hair) s3mt is cut; the eye is sealed by the nestling in its hole…”

P. Barguet[11] and William A. Ward[12] transliterated this sentence as follows: Hdq s3mt irt xtmt n t3 nb3b3.f, so having a verb (nb3b3), with unclear translation[13]. But if we take the final as n b3b3.f the texts has more sense: the nestling[14] is into its hole b3b3. This word can refer to the seven orifices on the face, of which two are the eye sockets[15] ; taking into consideration our context, it seem quite logical to think of b3b3 in this chapter as a way to referring to the eye socket. That allows to translate the sentence as « the eye is sealed (or closed) », since the nestling is inside the orbit (as it was a nest) and impedes the vision.

We need also to focus on a following sentence for ending the chapter that says: “Live the nestling that goes out from you…flies the fly and live Osiris…” This flight is strongly connected with the resurrection of Osiris-bird. When that one remains inside the nest-socket, the eye is sealed and that means no to access light, it is the moment of shadows and darkness (death). The chapter 1131 connects that with cutting the s3mt and after doing that the nestling flies and the eye can open; it symbolizes the capacity to see, the brightness after the darkness, the Osiris/deceased’s resurrection.

Sokaris, as a falcon, with the Udjat eye over him, spread his wings for flying up. Painting from the tomb of Pashedu in Deir el-Medina. XIX Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

That is a very solid idea in Ancient Egypt and dates back from the Old Kingdom; the dead king could reach the Hereafter as the eye of Horus, but he usually took the aspect of a bird, using the faculties of this animal for flying up[16].

Summing up, the main ideas we can take from these three chapters of the Coffin Texts are:

- The s3mt (lock of hair or just hair) is cut just before the final resurrection in ancient Egypt funerals.

- The Osiris’ resurrection is connected with the shave of the mourners.

- The cut of the s3mt is connected in Egyptian belief with the eye and the vision recovery.

[1] The offer of the Udjat eye will be the offer per excellence, so everything offered will be called “Eye of Horus” (A. Erman, 1952, p. 209).

[3] Reconstruction could be (n).f

[4] In ancient Egypt there were assimilation between Osiris and Sokaris.

[6] Name related to the uraeus (Wb I, 317, 11).

[9] R.O. Faulkner, 1962, p. 9, 5.

[11] P. Barguet, 1986, p. 665.

[12] W.A. Ward, 1975, p. 62.

[13] It seems to be a verb related to the eye of Horus (Wb II, 243, 14).

[14]  this sign is the image of the nestling into the nest

this sign is the image of the nestling into the nest

[16] Pyr., 1216 y 1770. Whitney M. Davies, 1977,p. 167.

![]() ). According to R. Briffault lunar goddesses become prominent in advanced periods of the culture, especially with the agriculture development[3]. It is a star related also with the magical power of women[4], as the magic practiced by Isis and Nephtys over the mummy to contribute to the Osiris’ resurrection. Because in the primitive belief the moon’s attributes are character and aptitudes of women[5], the star portrays the women’s nature, so, as reflect of the sun, the moon is the feminine complement of the king of stars, which in the mythic sphere was Hathor[6].

). According to R. Briffault lunar goddesses become prominent in advanced periods of the culture, especially with the agriculture development[3]. It is a star related also with the magical power of women[4], as the magic practiced by Isis and Nephtys over the mummy to contribute to the Osiris’ resurrection. Because in the primitive belief the moon’s attributes are character and aptitudes of women[5], the star portrays the women’s nature, so, as reflect of the sun, the moon is the feminine complement of the king of stars, which in the mythic sphere was Hathor[6].