It is impossible to avoid thinking of a relationship between the nwn gesture and the Nwn , the primeval chaos of the Egyptian cosmogony (It is also unavoidable to think on a play on words). The first one could easily be a way of coming back to the primeval moment, to the chaotic waters (Nwn) where the Primeval Hill came out from and where the Demiurge created the world.

At this point, we have to think of some other Egyptian rites with a renovating goal. It would also be possible that in those rituals exist similar practices. And we have found very interesting results looking at some documents related to two festivities: the Sed Festival and the Festival of the Valley.

Nwn gesture in Sed Festival.

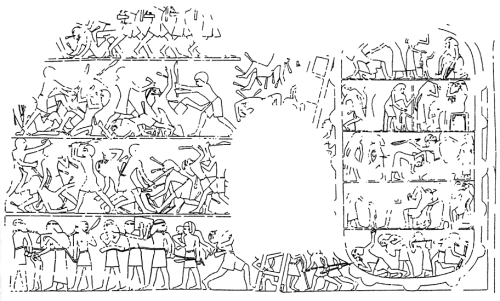

In the tomb of Kheruef in Thebes (TT192), from the reign of Amenhotep III, there is a relief of the Sed festival of that pharaoh. A group of women are making a dance in front of Amenhotep III, in some cases they are making the nwn gesture[1]. The inscription says that the women are stretching out facing the king and making the ceremony [Sed Festival] before the throne.

Dancers shaking hair in the Sed Festival. Tomb of Kheruef. Assassif. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

The inscription just over the dancers could be a song, whose meaning would be related to their movements[2]. This same ceremony and dance is represented in some talatats found in Karnak, where it was the scene of the Sed Festival of Akhenaton.

The Sed Festival was a ceremony for renewing the pharaoh’s power. The king had a ritual death and afterwards he came back to life with all his faculties and in perfect physical conditions for going on with his kingship. It had five main parts:

- The pharaoh is on a procession dressed with the Sed shroud

- Rites of renewing and rebirth.

- Homage is paid to the renewed king on his throne. He starts the new order of the world.

- The pharaoh visits the gods in their chapels.

- Ritual running of the pharaoh showing his physical vigour[3].

The Sed Festival has a Predynastic origin[4] and the god Sed could be an archaic version of Upuaut « The opener of the ways ». In the Palermo Stone the register related to the king Den shows the name of the god Sed written with the determinative of the Upuaut standard, the divinity that represents the king as the first-born son[5]. In addition it is interesting to notice how in the festival of Osiris in Abydos, the one avenging the death of his father was not Horus, but Upuaut[6].

We could maybe consider also that the Sed Festival in the Old Kingdom had some elements of the cult of Osiris[7]. In the Dramatic Ramesseum Papyrus, that tells the ascension of Sesostris I to the Throne of Egypt, we read that the erection of pillar djed (an Osirian rite) was a very important moment in the Sed Festival[8], there is also much iconography of the New Kingdom the relationship between the cult of Osiris and the Heb Sed[9].

This Festival is a death/resurrection ceremony, in which dancing women make an nwn gesture with their hair. What those dancers make with their hair could have a very deep symbolic meaning. The pharaoh is like a dead (although just hypothetically) and he has to revive. In this case the Sed Festival is a ceremony of death and resurrection, so those dancers maybe would be very close to the mourners in the funerary ceremony.

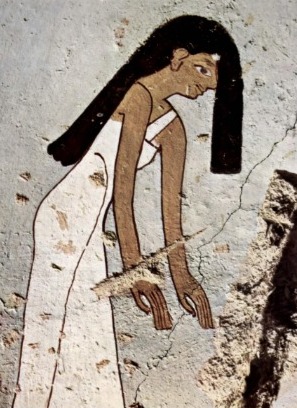

Mourning woman of tomb of Minnakht. Photo: http://www.1st-art-gallery.com

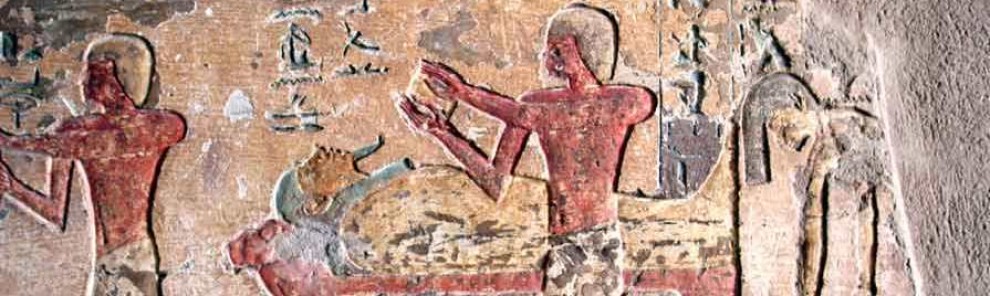

Dancing woman in nwn gesture. Tomb of Kheruef in Assassif. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

There was also a relationship between the Sed Festival and the beginning of the flood[10]. The Sed Festival was celebrated before the appearance of Sothis (the Egyptian name for the star Sirius) in the sky announcing the coming of the annual flooding of the Nile that was the beginning of the New Year in Ancient Egypt. The flood is one of the best examples of annual renewing for the Egyptians. The water of the flood, as the water of Nun in the Egyptian cosmogony, contents the active ingredient for the new life: the mud that fertilises the ground and grants the maintenance of Egyptian people. Also in the tomb of Kheruef we read: “…Appearance of (king Amenhotep)…for resting on his throne that was in his Sed palace, built by him on the west side of the city. Open the way through S.M. over the water of the flood, for bringing the gods of the Sed Festival”[11].

In a statue of the New Kingdom we read how the owner is « beloved of Sothis, Lady of the Sed Festival » and in the ceiling of Ramesseum Ramses II sees Sothis “at the beginning of the year, the Sed Festival and the flood”[12].

The Heb Sed was celebrated neither during the rise nor during the decrease of the flow, but in the driest moment[13], before the rising of Sothis and the arrival of the flooding. The Sed Festival announced the future waters, so it was the prelude of the new era, the new revival after the drought. And we have seen that in the rite, a dance with the nwn gesture took place.

In the Sed Festival, the pharaoh was like a ritual dead who had to come back to life[14], so he was assimilated to Osiris. That would explain the Osirian tinge of the ceremony. The king, symbolically dead, received the rites that Isis, Nephtys, Anubis, Thot and Horus made over the corpse for reviving[15]. In this regenerating ritual appears the nwn gesture as a part of the practices for the rebirth of Osiris/pharaoh.

[1] Fakhry, 1943, Pl. XL, p. 497.

[2] Fakhry, 1943, p. 497. In the temple of Bubastis there are some fragments relating to the Sed Festival; one of them shows a group of dancers with a small part of this song. (Naville, 1892, Pl. XIV)

[3] LÄ V, col. 785.

[4] LÄ V, col. 782. The Sed Festival is documented from the beginning of I Dynasty in the Narmer macehead and also maybe in the Scorpion macehead (Cervelló Autuori, 1996, p. 209, n. 154).

[5] Cervelló Autuori, 1996, p. 208, n. 150.

[6] Cervelló Autuori, 1996, p. 210.

[7] LÄ V, col. 786.

[8] LÄ V, col. 786; Barta, 1976, pp. 31-43.

[9] LÄ V, col. 786.

[10] Hornung und Staehelin, 1974, p. 56.

[11] Translation of Helck, 1966, p. 78.

[12] AH 1, 1974, p. 58.

[13] AH 1, p. 58.

[14] Mayassis, 1957, p. 226.

[15] Mayassis, 1957, p. 68.