Related to the lock of hair s3mt we have seen two important points:

- To keep the lock of hair s3mt intact is a hope of new life for the deceased.

- The lock of hair s3mt seems to be victim of ablation, just in the moment when the dead gets his head back again (see chapter 532 of Coffin Texts).

It is interesting to notice that the Egyptian verb utilised for “cut” the s3mt is Hsq, which also means “decapitate”[1] ; so the whole sentence could also be translated as « behead the lock of hair s3mt ». The act of beheading is very close to sacrifice. The idea of sacrifice is very common in Ancient Egyptian religion, mainly the sacrifice for avoiding dangers or the slaughter as revenge. But our area is funerals, dead, and renovation, resurrection, regeneration. Could we think of a symbolic sacrifice made in funerals for benefitting the deceased? Or do we know sacrifices made in Ancient Egypt with renovation finality? Yes, we do and we know a victim’s name: tekenu. This enigmatic figure appears in Sed Festival rites and also in funerary ceremony[2]. In both cases he is a man wrapped in a kind of shroud sit or in foetal position and his role is still too unknown.

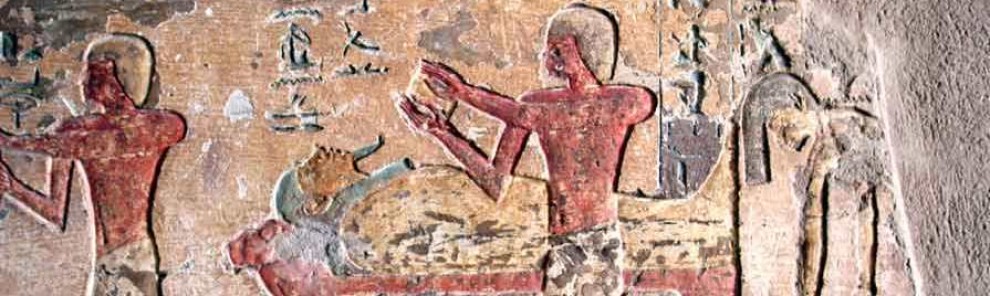

Tekenu wrapped in a shroud and in foetal position over a sledge. Painting from the tomb of Ramose in Gourna.XVIII Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

According to some scholars there was in ancient Egypt a prehistoric rite where a royal adolescent was sacrificed[3] and wrapped into an animal skin[4]. After the young’s death, the king would cover himself with that animal skin obtaining so the vitality the teenager had impregnated[5]. This gesture would symbolize the king’s return to his mother womb and the following rebirth; granting this way the renovation of the sovereign. The human sacrifice of Sed Festival, real or symbolic, is proven from the scenes of some slabs dating from the early I Dynasty. Maybe this practice of murdering was abandoned during that same I Dynasty and had just a symbolic dimension. After a previous symbolic sacrifice (human or animal)[6] the Pharaoh would be wrapped in a skin/shroud for getting the vitality needed.

It seems that in the heb Sed, the sacrifice had two values, one Osiriac and propitiatory and another ones Sethiac and expiatory. Both, although apparently opposed are complementary, since the death of Osiris requires next Seth’s. On one hand Osiris’ death reflects vileness and on the other hand Seth’s death means the victory of the good over the evil. Two faces of the same coin, where the king dies and comes back to life as Osiris did, while the meanness is destroyed as was Seth in the myth[7]. The tknw of some images of New Kingdom as a huddled person on a sledge could be in origin that human victim of archaic times sacrificed for the benefit of the sovereign, replaced in funerals for the benefit of the dead.

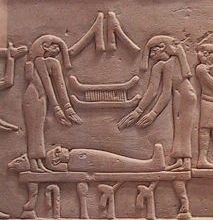

One of the first documents of Sed Festival is the tablet of king Djer found in Abydos by Petrie. The entire scene is disposed in there registers and in the first row is one of the little documents in iconography of a human sacrifice in Ancient Egypt.

Tablet of king Djer. Photo: http://www.ancient-egypt.org

The second register shows two possible victims represented in a conventional way, the surprising thing is that both have a frontal trace. What did the sculptor want to represent? The answer is not so easy. A priori it could remember the image of the so common Egyptian image of the enemy, usually interpreted as gripping his own stream of blood flowing from his front.  But, makes it sense to hold a liquid element with both hands? Would not be more logical to think of a more solid element to catch with both hands?

But, makes it sense to hold a liquid element with both hands? Would not be more logical to think of a more solid element to catch with both hands?

[1] Wb III, 168, 16.

[2] Designation tknw for the victim in funerals appears in New Kingdom.

[3] A king’s son, that is a prince (msw nsw).

[4] The use of animal skins is common in initiation ceremonies (J.L. Le Quellec, 1993, p. 335)

[5] Enel, 1985, p. 204.

[6] J. Cervelló Autuori, 1996, p. 211.

[7] J. Cervelló Autuori, 1996, p. 209.