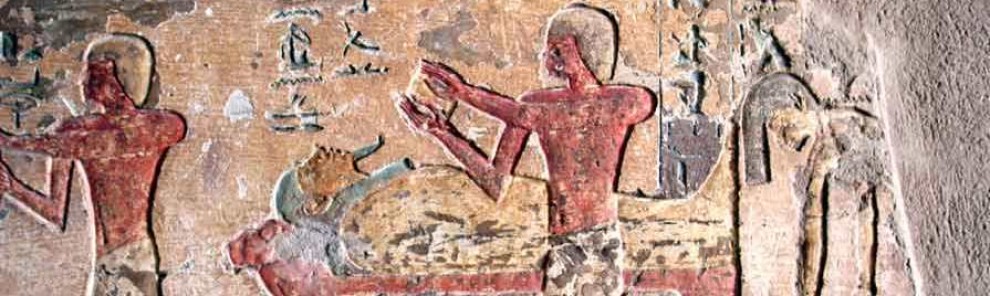

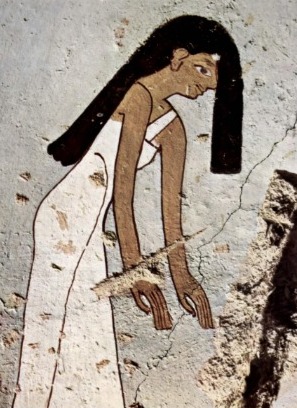

If tears are identified with the water and the flood, could we then think of the hair as the shores and the vegetation? If so, we would have a very symbolic image of Egypt: the tears drooping from the eyes would be like the Nile, while the hair at both sides of the face would be both banks of the river.

Mourners with tears falling from their eyes (water) and hair on both sides of the face (vegetation). The image could be a metaphor of the Egyptian landscape, made up by the Nile and the both shores of the river. Painting from the tomb of Ramose in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

At that point it is meaningful the fact that in Egyptian the expression for “vegetation” was « the hair of the earth ».

In chapters 168 and 562 of the Coffin Texts both banks of the river are considered as the manes shenu of Isis and Nephtys[1]. Chapter 168 says :

« Join both banks. The hair of Isis is tied to the hair of Nephtys (and) vice versa. Fluids[2] have no boat. River is dry. Geb has taken the water up. Both hands of Smsw are united over the lungs of Both Ladies »

Fluids[2] have no boat. River is dry. Geb has taken the water up. Both hands of Smsw are united over the lungs of Both Ladies »

In chapter 562 we also read:

« The hair of Isis is united to the mane of Nephtys …The West bank joins the East bank. Both united when they were separated. Then I passed across…I reunited with both sisters, they do not suffer anymore… »

To unite both hairs shenu means to get both banks together, and that would allow the dead to pass to the Hereafter without needing any boat. The hair of Isis and Nephtys was a means for getting the resurrection.

But we can move a step forward. The union of both shores symbolised the reconciliation of the two sisters. According to a version of the legend, Osiris cheated on Isis with her sister Nephtys, of which union Anubis was born. Obviously that caused discord between both sisters; in the symbolic dimension the union of both manes was the end of the discord, as we can read in Book of the Dead: “Pray Osiris …both shores are reconciled…he has caught aversion from their hearts for you, they hug each other”[3].

It is also interesting to indicate that in chapter 167 of Coffin Texts the mourners give their hair sema , while in the following 168 the hair shenu of Isis and Nephtys get tied, so we could wonder if they are two successive acts or one same gesture means two different actions.

The Papyrus Salt 825 in the British Museum (from the Late Period) contents the rites for preserve the life[4], which were a group of practices made during the month of Thot[5], and we can read in it:

(I,1) “The night is not lighter[6] and the day does not exist[7]. One mourning is made twice in the sky and in the earth (I,2) Gods and goddesses put their hands over their heads, the earth is devastated (I,3) the sun does not rise and the moon is late, it does not exist. The Nun staggers ;(I,4) the earth frets; the river is not navigable anymore. (I,5)…Listen. Everybody is moaning and crying. The souls, (I,6) the gods, the goddesses, people, the Akhu, the dead ones, small animals (I,7) and big ones, the… cry, cry so much,…” [8].

For the expression “the earth is devastated” the scribe wrote:

The verb fk means « be bald »[9]. The wasteland is an earth without hair. The absence of hair is a parallel of the absence of herb[10]. So, the hair shenu of Isis and Nepthys could easily be assimilated to the vegetation.

The verb fk means « be bald »[9]. The wasteland is an earth without hair. The absence of hair is a parallel of the absence of herb[10]. So, the hair shenu of Isis and Nepthys could easily be assimilated to the vegetation.

Life and death in Ancient Egypt were made conditional to nature and the seasons. The inundation that extended the mud all over the land and fertilised it, made possible the vegetation to grow up once the water retired. That was during peret, the season of sowing. If the hair element was before related to water, now it is linked to plants as the result of the fertilization of the land thanks to the regenerating waters.

The funerary cult is usually influenced by the cult to fertility and the “sacrifices and/or offers to the ancestral souls are taken from agricultural rites”[11]. The Osiris rite is an agricultural and lunar ritual, where lunar cycle and agrarian rites are mixed. As the moon does, the plants also have a cycle of birth, growing, death and resurrection. Cyclic also are the seasons (from drought to fertility). Moon, plants and seasons are cyclic; for that reason in Egyptian religion the lunar divinities are also vegetation gods.

In Ancient Egypt there were three seasons: akhet (inundation), peret (sowing) and shemu (harvest). The Egyptian year stated with the flooding of the Nile and the first month of akhet was tekh  , word which meant « get drunk ». Inebriation and inundation together makes us think of concepts as chaos and orgy and also of the disorder of the hair sema, since the verb tekhtekh

, word which meant « get drunk ». Inebriation and inundation together makes us think of concepts as chaos and orgy and also of the disorder of the hair sema, since the verb tekhtekh  (duplication of tekh) means “to dishevel”[12]. At the end of the akhet season (in the month of Khoiak) took place the festival for Osiris.

(duplication of tekh) means “to dishevel”[12]. At the end of the akhet season (in the month of Khoiak) took place the festival for Osiris.

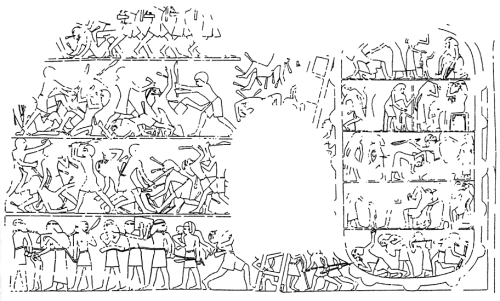

Osiris, the mutilated god, came back to life in his shape of moon and in his shape of plant, so both cases were perfect images of resurrection. In those rites first some grains were put into moulds with the shape of the mummy of Osiris, where those grains would become plants. The 23rd of that moth took place a ceremony symbolizing the search and collection of the pieces of the corpse of Osiris and the embalming made by Anubis in the Golden House, which was also the place where the « Ceremony of the Opening of the Mouth » was carried out. According to some documents of Middle and New Kingdom, the 23rd day on Khoiak month was also called the day of the “Great Mourning”. The night of 25th took place the Lamentations of Isis and Nephtys, songs which read aloud the women representing the two goddesses. Just after that mourning rite, in the sunrise of 26th, was the resurrection of Osiris.

So, the akhet season started with the inebriation, the disorder, the chaos, and the primeval waters and finished with the fertilisation of the land, the end of the darkness and the resurrection of Osiris after a Mourning Rite made by Isis and Nephtys.

The hair of Isis and Nepthys had a role related to the cycle of life: first the sema is identified with the water, the inundation, the Nun, as a receptacle of regenerating principles; afterwards the hair shenu is assimilated to vegetation, as the product of the creation and as a manifestation of life. This would explain succession of chapters 167 and 168 in the Coffin Texts.

Once again hair is an element related to life; although we have seen now two different terms (first sema and then shenu) we are not moving away from the funerary and mourning context. The verb sheni means « suffer » and related to it is the name of the goddess Shentayt[13]. This divinity, which is documented from XIX dynasty, was assimilated to Isis as a mourner and widow of Osiris and appears in funerary rites of regeneration and purification oh him[14].

[1] Vegetation grows up on shores

[2] Mention to the putrefied Osiris corpse.

[5] When the ceremony took place there also were some other funerary festivities (Derchain, 1964, p. 63).

[6] The moonlight does not illuminate.

[7] Darkness caused by the death.

[8] Derchain, 1964, p. 137.

[10] In agricultural people the growing of the hair is linked to the image of the growing of alimentary plants; and the same idea of growing up is related to the idea of rise. (Chevalier et Gheerbrandt, 1969, p.369).

[11] Elíade, 1970, p. 297.

[14] Cauville, 1981, pp. 21-40.

![]()