The fact of being a secret ceremony would explain why it is so rare to find images of the two mourners in the role of Isis and Nephtys carrying out the mourning ritual. The iconography shows them crying next to the mummy, but it is not usual to see what exactly they do.

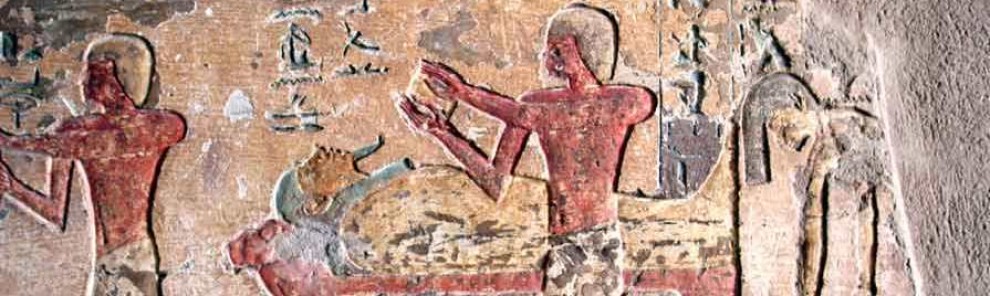

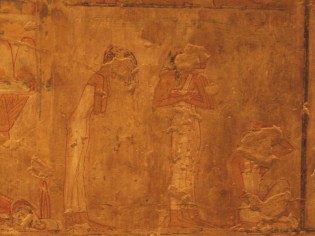

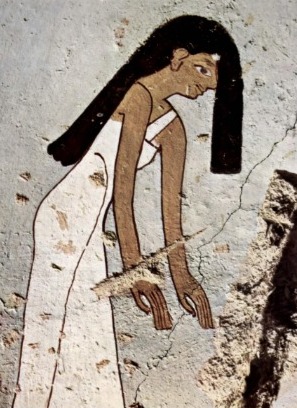

On the right the mourner in nwn gesture towards the corpse. Scene from the tomb of Renni in el-Kab. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

Some of the most explicit images of what the mourners do with their hair over or in front of the mummy are the stele of Abkaou (XI Dynasty), the tomb of Renni in el-Kab (XVIII Dynasty), the funerary temple of Seti I in Dra Abu el-Naga (XIX Dynasty) or the tomb of Ramsés IX (XX Dynasty); being scenes included in the coffin we could also put in this group the representations of Isis and Nephtys pulling their frontal lock of hair in the coffin of Ramsés IV (XX Dynasty) and in the coffin of Nes-shu-tefnut (Ptolemaic period).

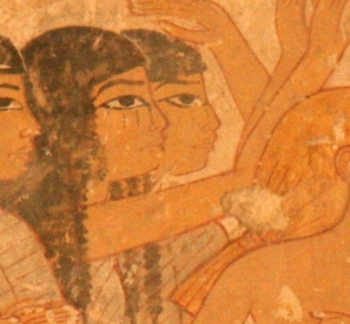

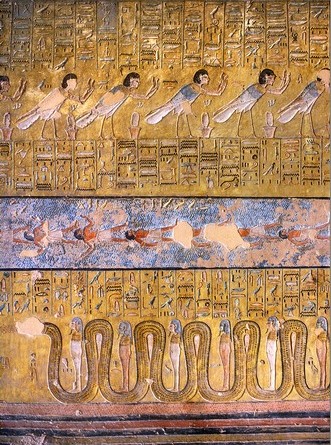

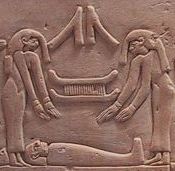

Isis and Nephtys making nwn m gesture. Sarcophagus of Royal Scribe Nes-shu-tefnut from Saqqara. Ptolemaic Period. Kunsthistorisches Museum in Wien. Photo: http://www.globalegyptianmuseum.org

Even the Opening of the Mouth rite of the tomb of Rekhmire does not give us a defined idea of the performance these women did it is the most complete scene of the whole ceremony that ancient Egyptians have left to us, but it is not clear what these two women did, since the mourners appear with a passive gesture. However, thanks to the funerary literature, we know that already from the Old Kingdom they performed a mourning ceremony screaming, crying and shaking or pulling hair. So, Rekhmire wanted the resurrection rites to be reflected in his tomb, but the artist might have a sacred limit, because the divine secrets must be concealed as a sign of respect[1].

According to the sources we have seen all along this work we have proofs of the following:

- The mourning rite was a part of the Opening of the Mouth ceremony.

- The mourning rite could be made by two women in the role of Isis and Nephtys or just by one mourner in the role of Isis (as Osiris’ wife), reproducing a passage of the Myth of Osiris.

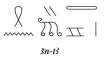

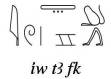

- In this mourning ritual the hair of the mourner(s) was the main element.

- This mourning ritual consisted not just of crying for the death of Osiris (the deceased), but of a gesture made with the hair.

- This gesture could be to shake the hair forwards and cover the face with it (nwn) or to pull the frontal lock of hair (nwn m).

- According to the iconography these two gestures were made over or in front of the corpse, so in the deceased’s direction.

There is no evidence in iconography, or in the funerary texts that both gestures were done together. It seems that in the mourning rite the mourner(s) did one or another. On what did the choice depend? We do not know.

At this point we wonder in which moment of the Opening of the Mouth ceremony did the mourners made the nwn or the nwn m gesture. Mostly the iconography shows the mourner(s) in the moment of the ox sacrifice, as we can see in the tomb of Rekhmire or in TTA4 and TT53.

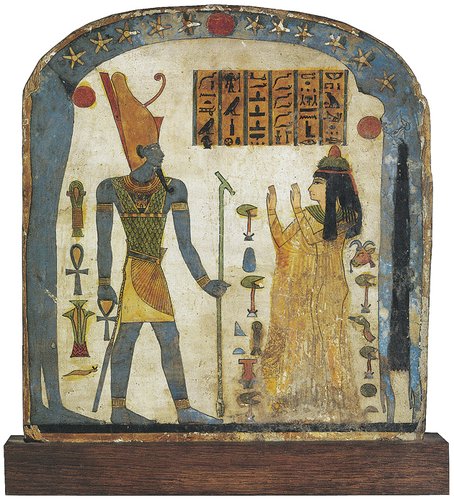

Sacrifice of the ox with the presence of the mourner. Painting from the tomb of Rekhmire in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: Mª Rosa Valdesogo Martín.

Thanks to the funerary texts we know that slaughtering the ox and mourning were not made at the same time. The Pyramid Texts give us a clue of what was first: “…the souls of Buto rock for you; they beat their bodies and their arms for you, they pull their hair for you. They say to you: Oh, Osiris you have gone and come back, you were sleepy and have waked up, you were dead and you have revived…Stand up, look what your son has done for you…he has beaten for you the one who beated you as a bull, he has killed for you the one who killed you as a bull sm3[2] may the mourning stop in both palaces…you go up (Osiris) to the sky and you are like Wpw-W3wt[3]. Your son Horus leads you over the heaven’s ways…”[4].

Reading this passage it seems that we find the following sequence:

1. The souls of Buto are Isis and Nephtys, so the mourners shake and/or pull their hair. We are in full mourning ritual.

2. Horus gets into the drama. That means that Isis has already conceived him and he could then revenge his father’s death. In the funeral it might be the moment of the sacrifice of the ox, as scapegoat. It remembered the fight between Horus and Seth and the victory of the falcon god.

3. Once the animal has been slaughtered, so the death of Osiris revenged, the moan stops. In this moment the deceased receives the foreleg and the heart of the ox and the Udjat eye as a symbol of the final resurrection. The end of the mourning was the cut of the s3mt. And maybe then was also when the mourner(s) were shaved and a lock of hair, assimilated to the healed lunar eye, was offered.

4. The Osiris’ rebirth is a fact.

If the sacrifice of an ox was the revenge of Horus it seems logical to think that the gesture of shaking hair was done before it. One of the meanings of this gesture was to allude to the moment Isis, as a kite, set on Osiris’ phallus for conceiving Horus. Once the heir was there, someone could revenge the Osiris’ death; it was the moment of the fight between Horus and Seth, which ended with the death of this one and the resurrection of Osiris. So firstly the mourner(s) started the gesture nwn towards the mummy; as the hair covering the face could also be a way of remembering the chaos and darkness, which in the legend was the battle between Horus and Seth, in some moment of this mourning rite, when the two mourners (kites) were still making the nwn gesture, started the ox’ slaughter. Once the animal had died, the two mourners (Isis and Nephtys) would stop the nwn gesture.

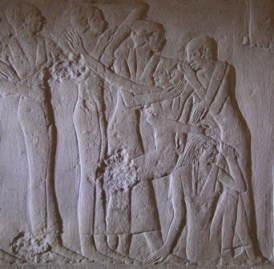

Sacrifice of an ox in the funerary ceremony. Painting from the tomb of Menna in Gourna. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

Taking into consideration that the mourning ritual and the ox’ slaughter were a reproduction of a passage of the myth of Osiris, it seems quite logical to place them at the end of the Opening of the Mouth ceremony, after other practices as for instance the tekenu ceremony. This is the way it appears in the tomb of Rekhmire. The tomb of Menna (TT69) has also a scene of the Opening of the Mouth where the tekenu practice appears at the beginning.

But in the tomb of Renni in el-Kab (EK7) there is a different version. On the east wall we can see how one mourner is making the nwn gesture towards the mummy during the Opening of the mouth ceremony.

On the right the mourner with short hair is wrapping someone. Scene from the tomb of Renni in el-Kab. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

In the upper register a woman with no mane, so the mourner appears wrapping with a kind of clothing a masculine figure. Would it be the early stage of the tekenu rite? So it seems; because the following image shows the tekenu being transported on a sledge while behind him stands the Drt with short hair.

The tekenu on a sledge, behind we can see the mourner (Drt) with short hair. Scene from the tomb of Renni in el-Kab. XVIII Dynasty. Photo: http://www.osirisnet.net

If so, then the mourning ritual with the hair would have been made before it. Why? Maybe these two practices made in the Opening of the Mouth ceremony had not an orthodox order or maybe the artists did not knew so much so they could represent the ritual as it was.

[1] S. Mayassis, 1957, p. 40.

[2] The bull sm3 is a bull for sacrifice that was assimilated to Set (Wb IV, 123, 17). It is interesting to notice the same phonetic as the word for hair sm3, which we know was related to darkness and chaos.

[3] The One who opens the Ways.

[4] Pyr., 1004-1010; 1972-1978